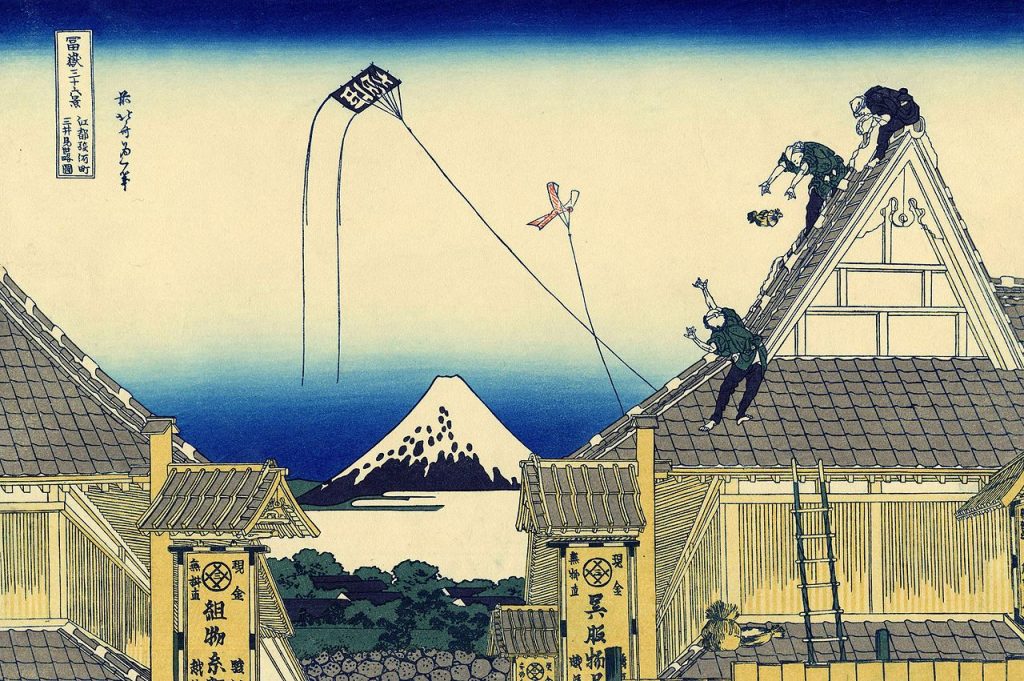

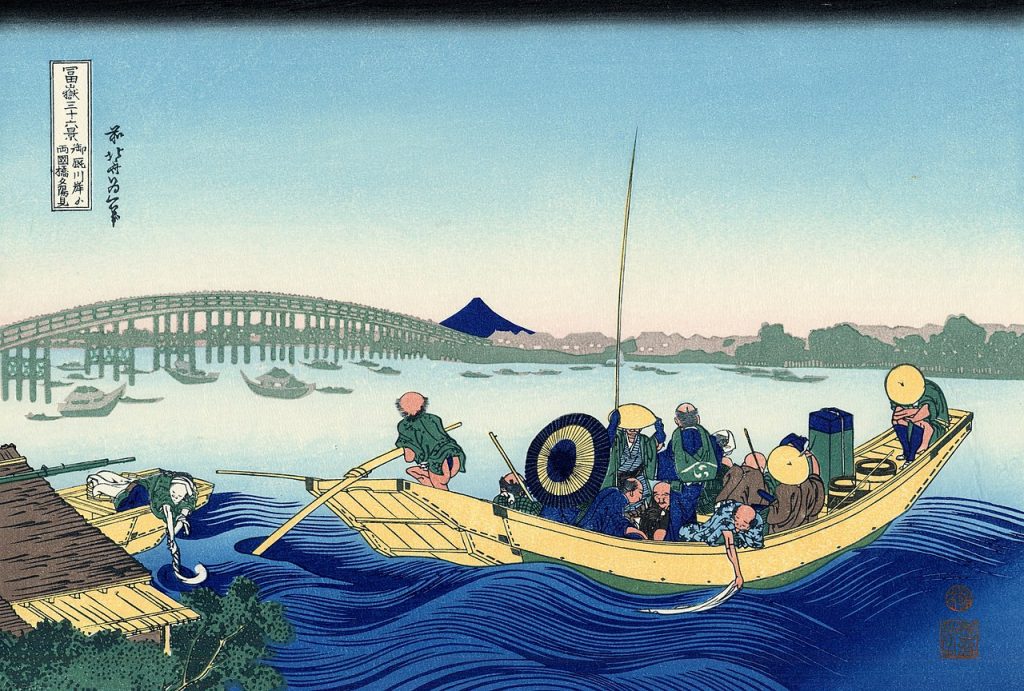

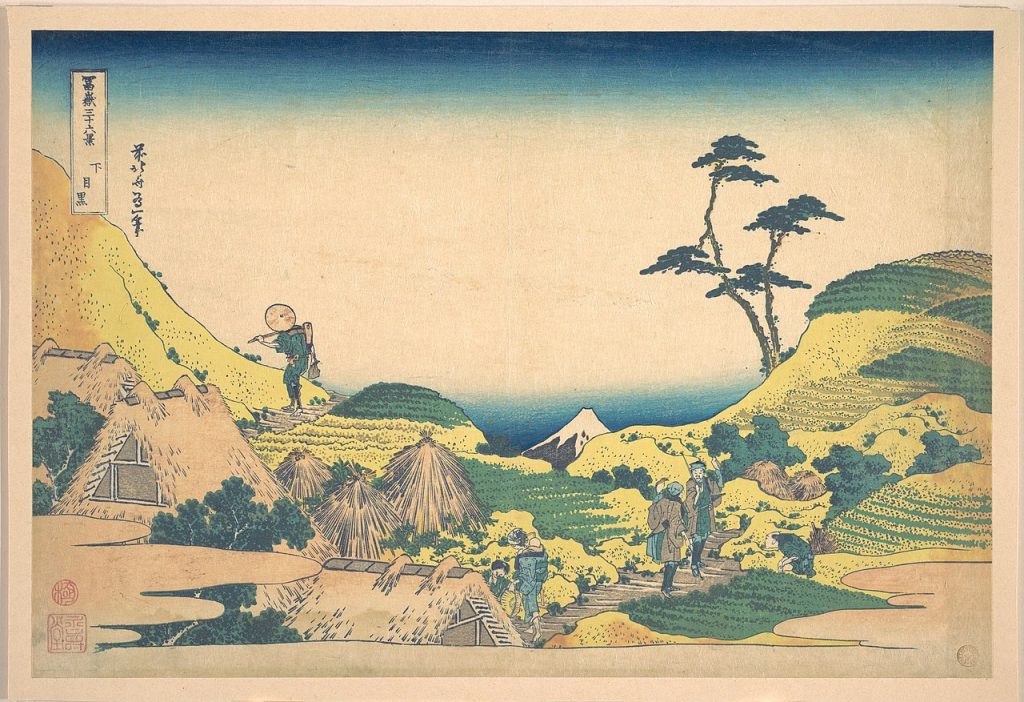

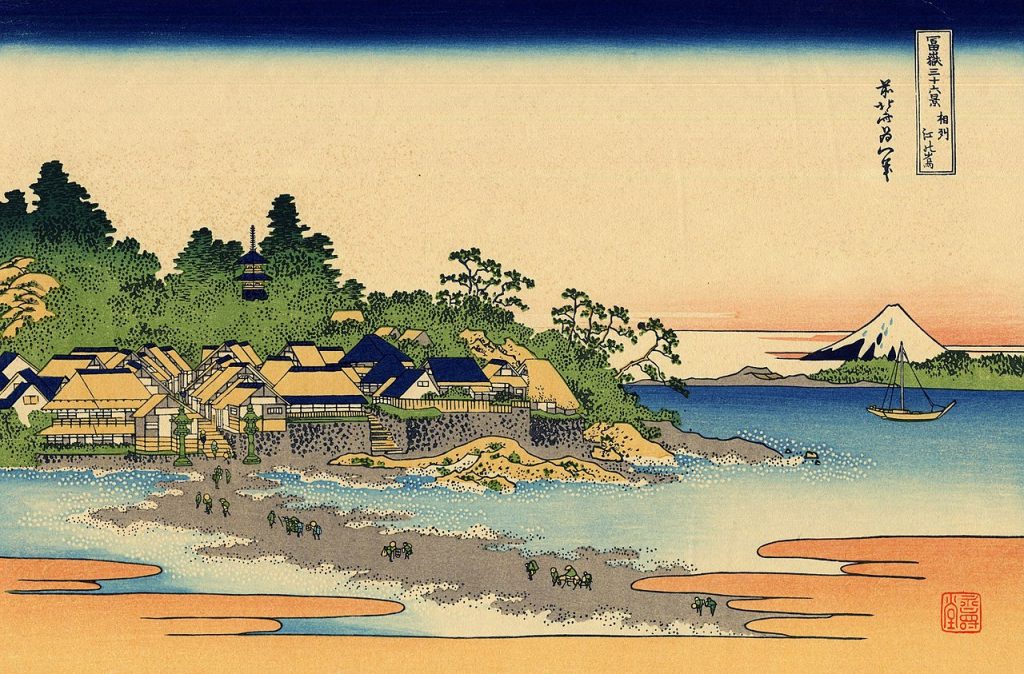

Thirty-six sketches of the world, through the brush-strokes of Japan.

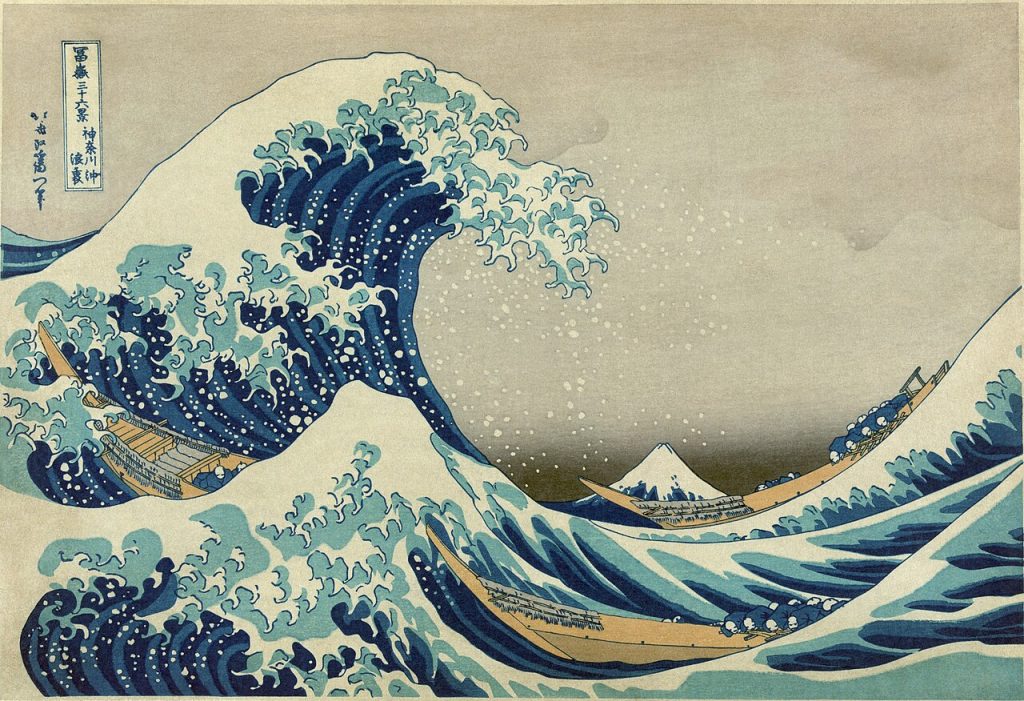

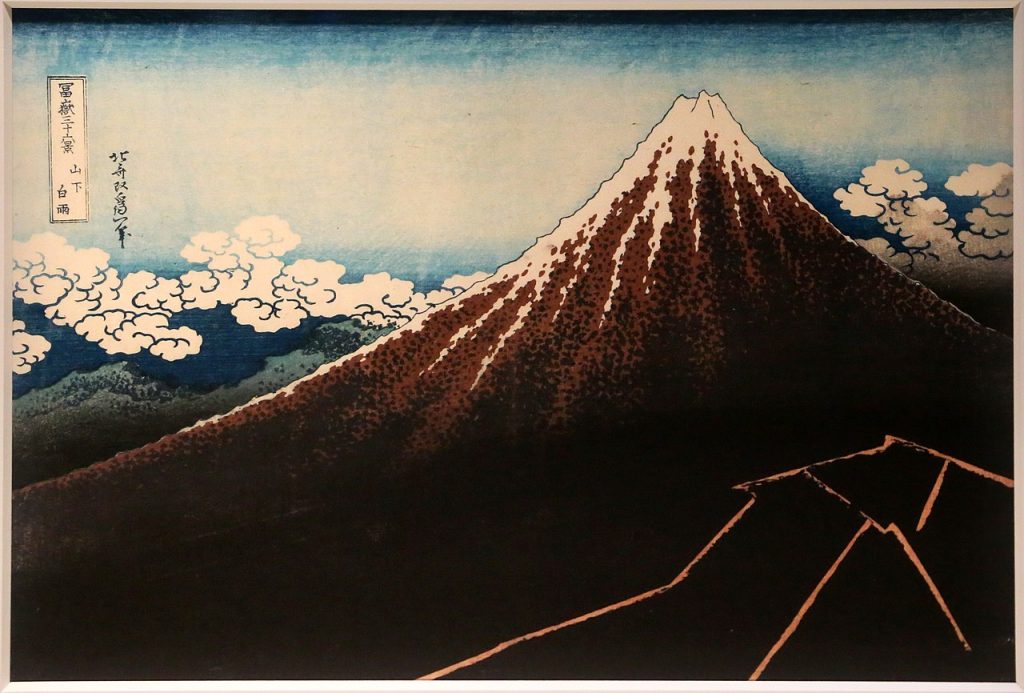

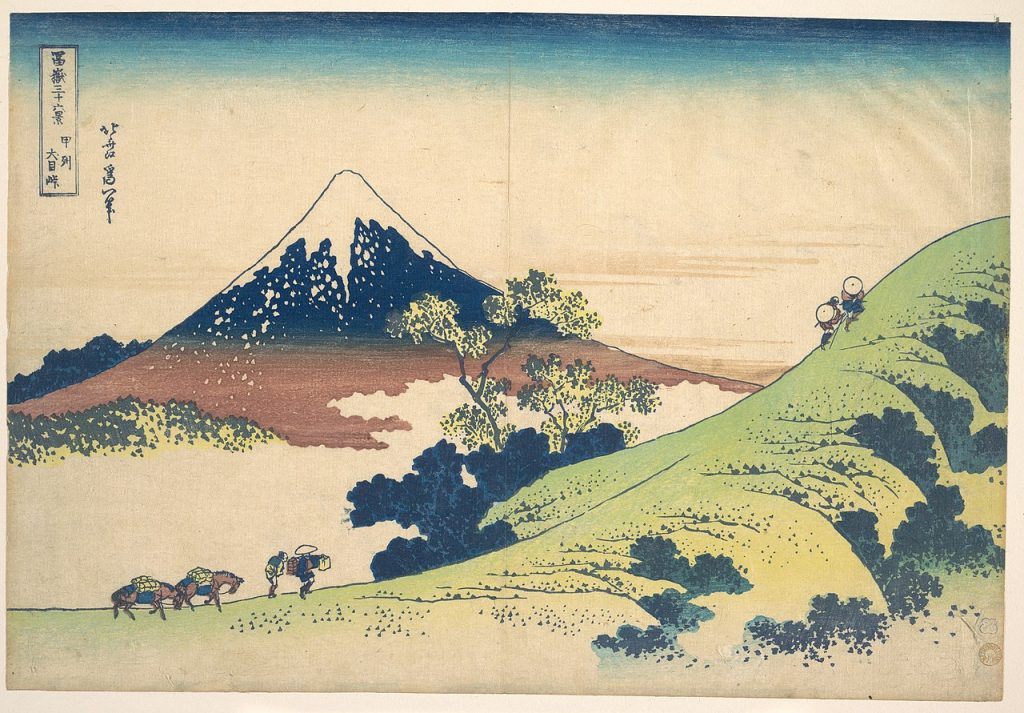

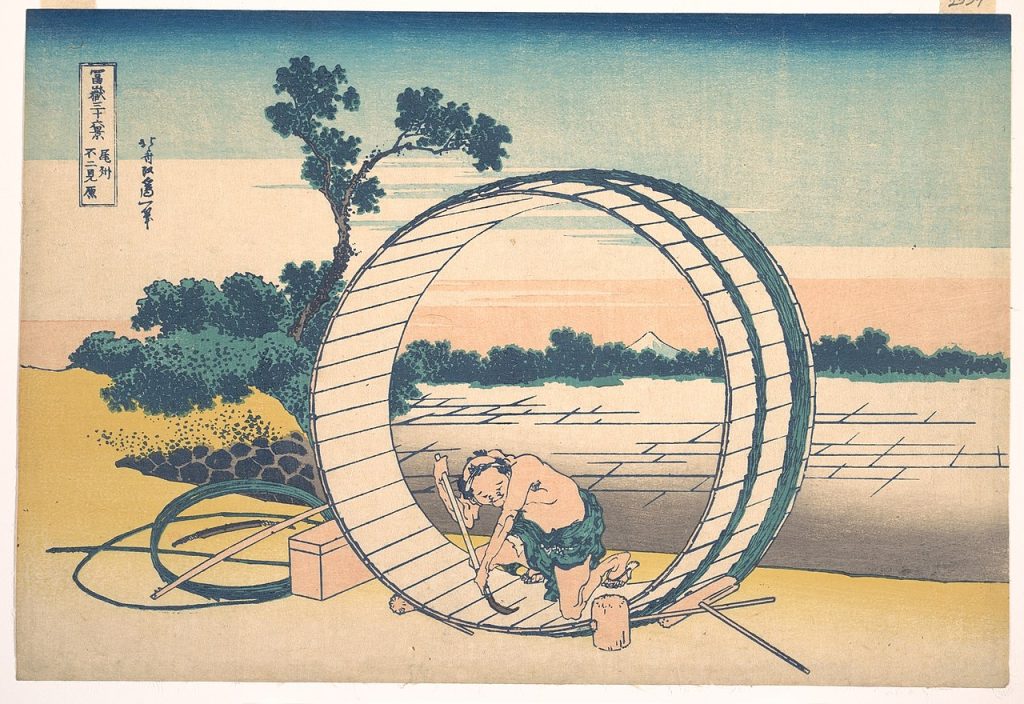

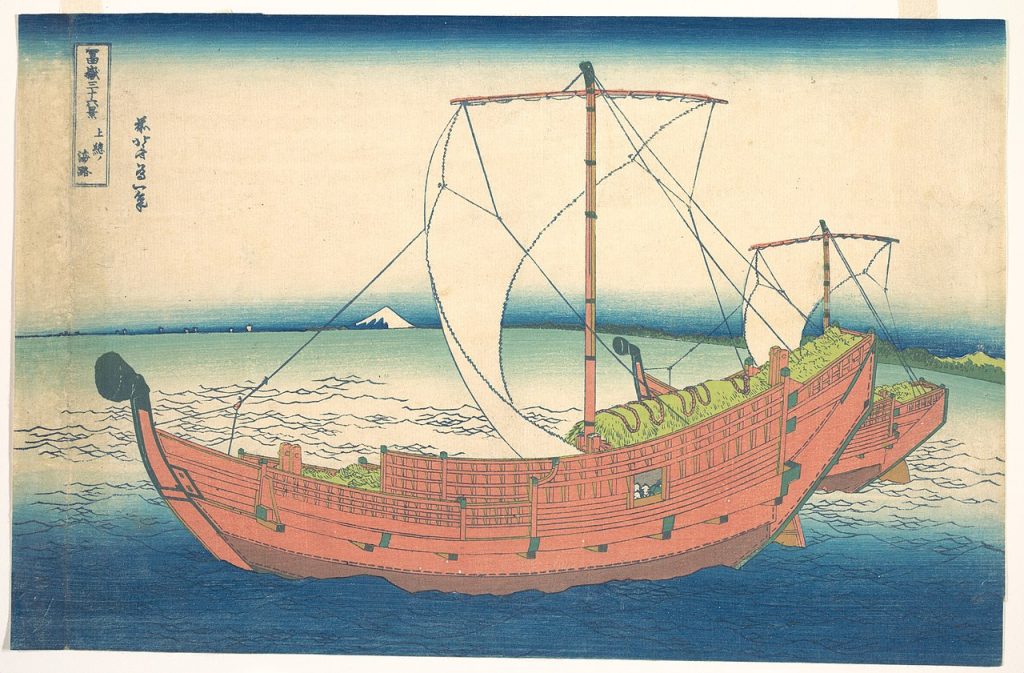

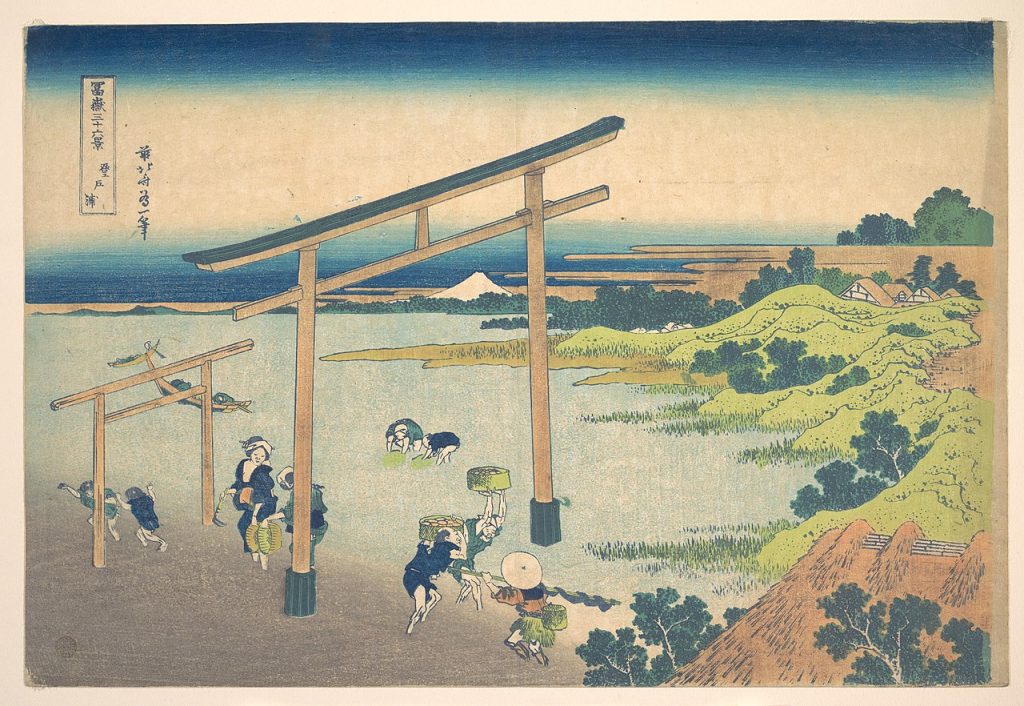

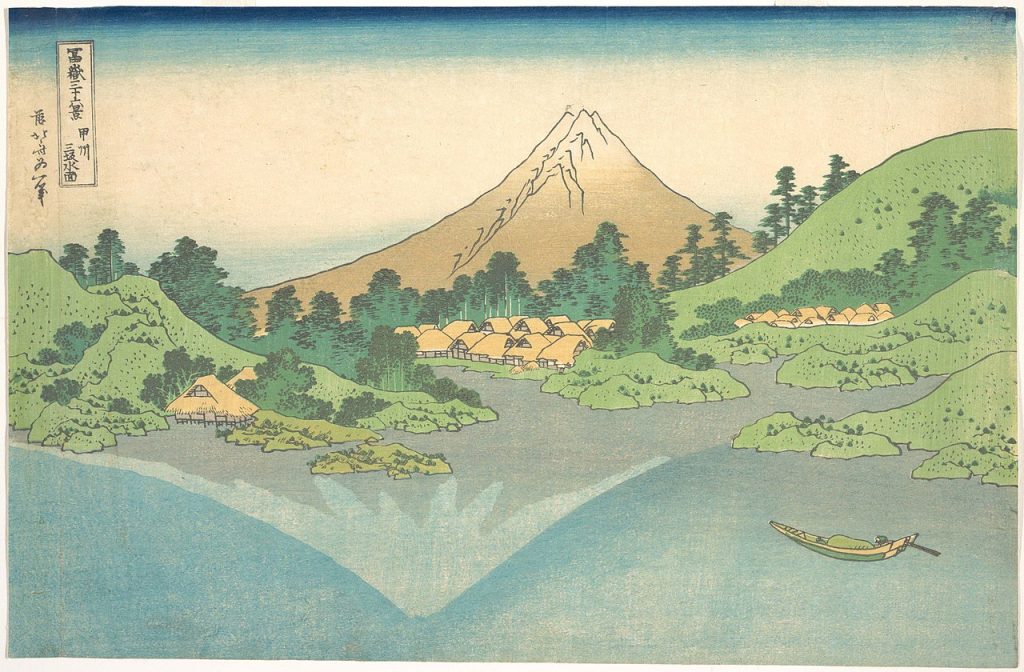

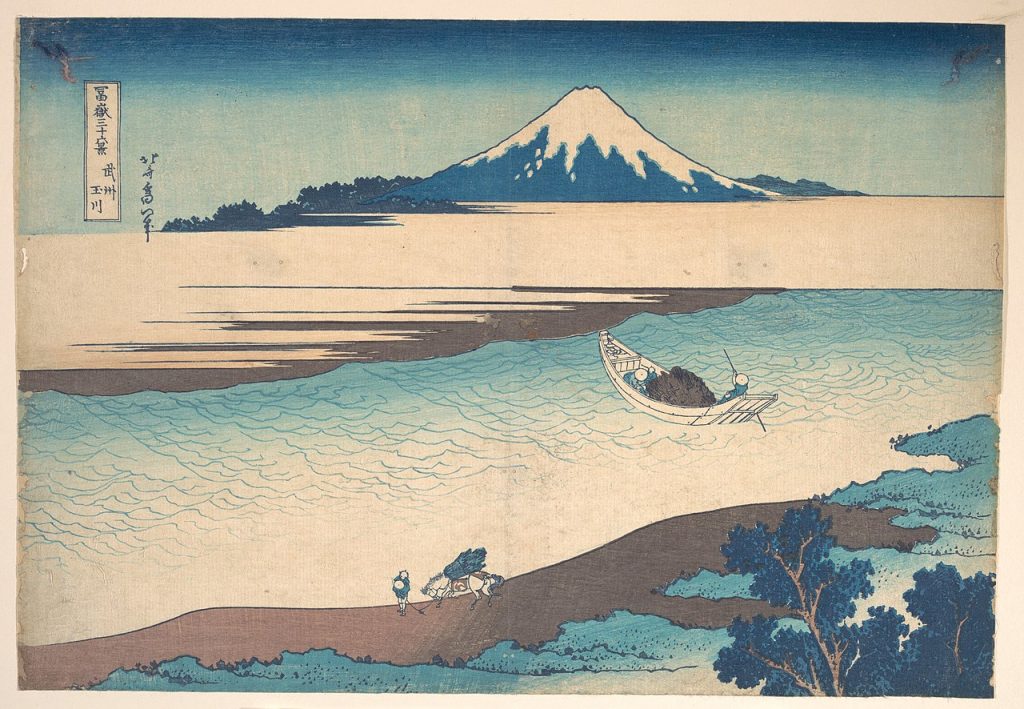

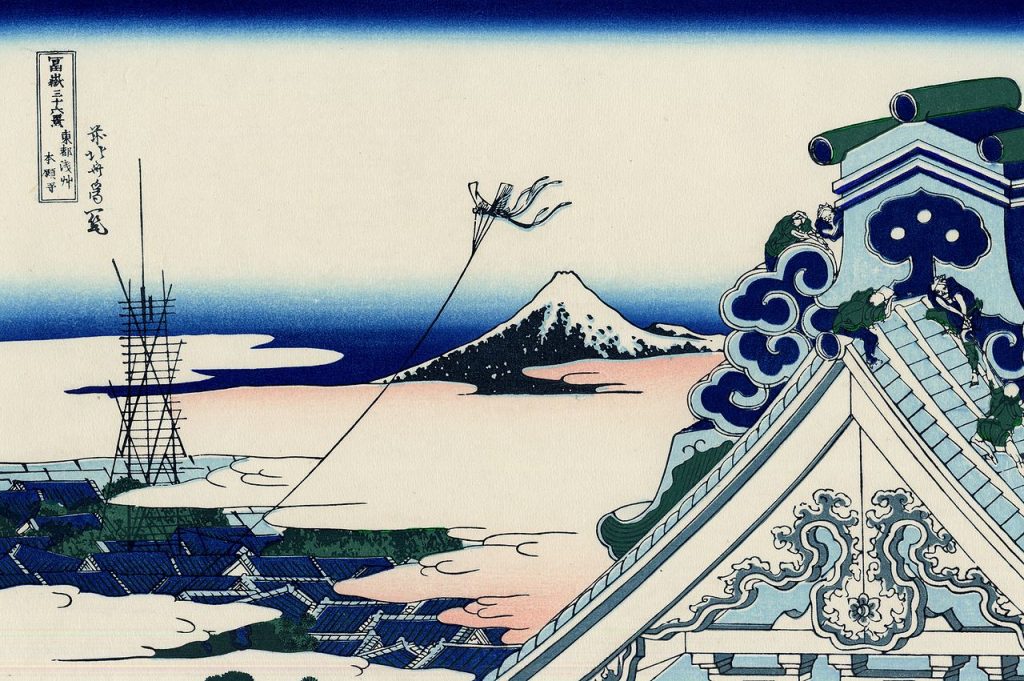

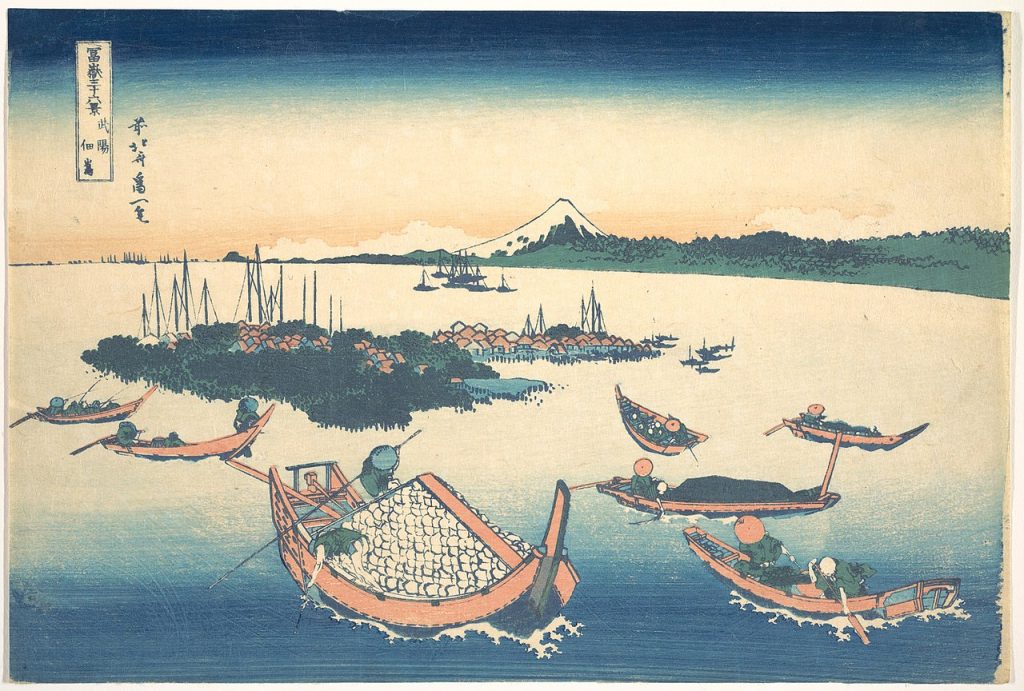

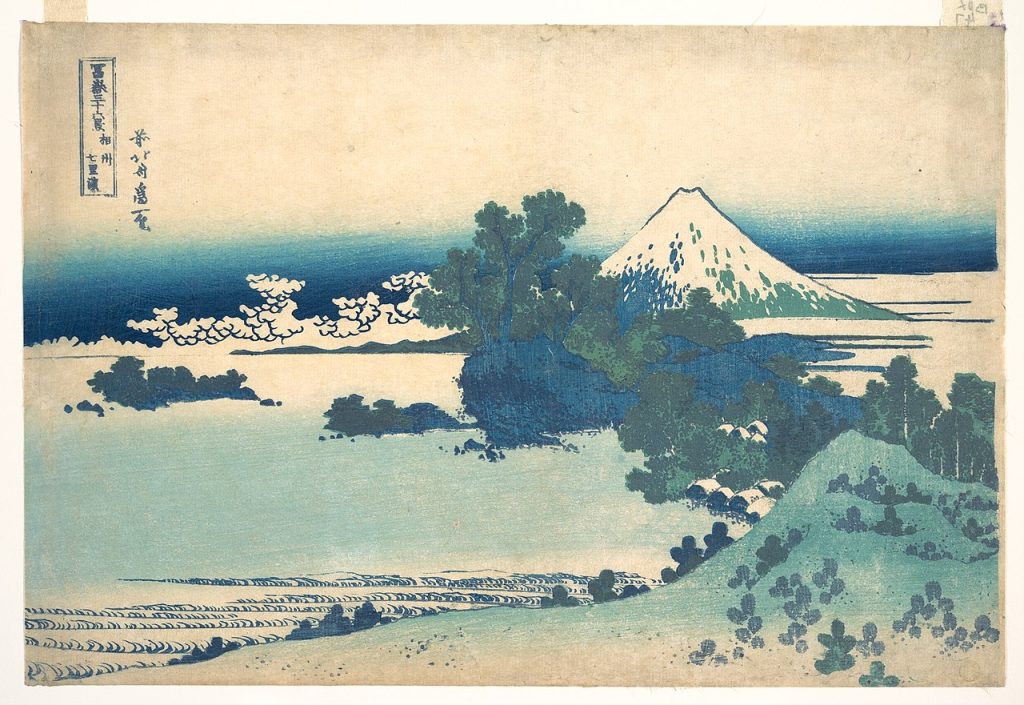

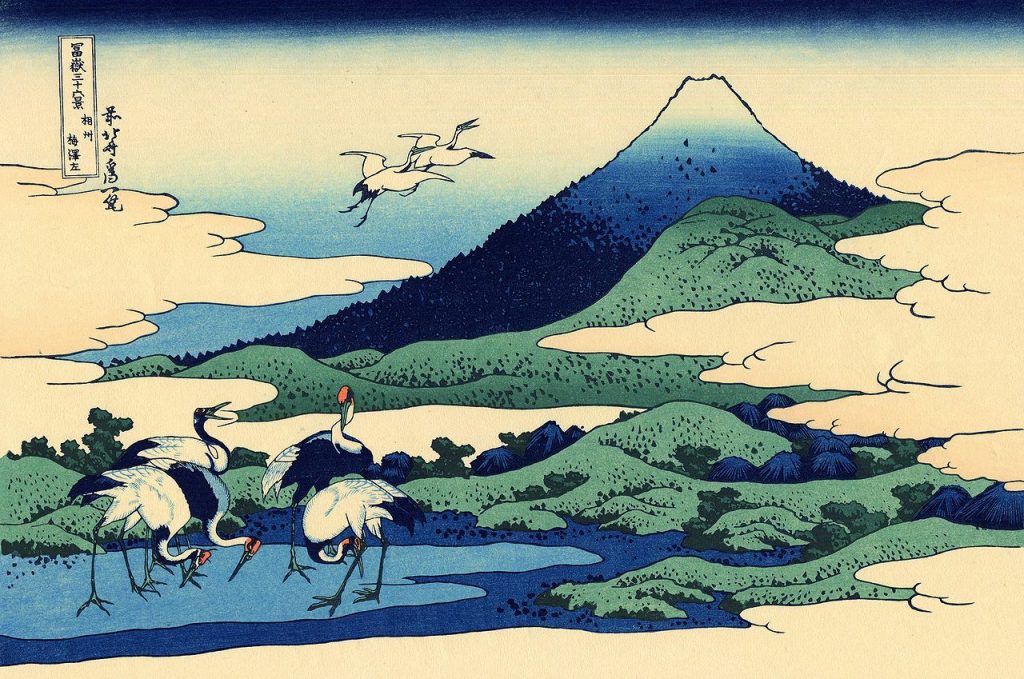

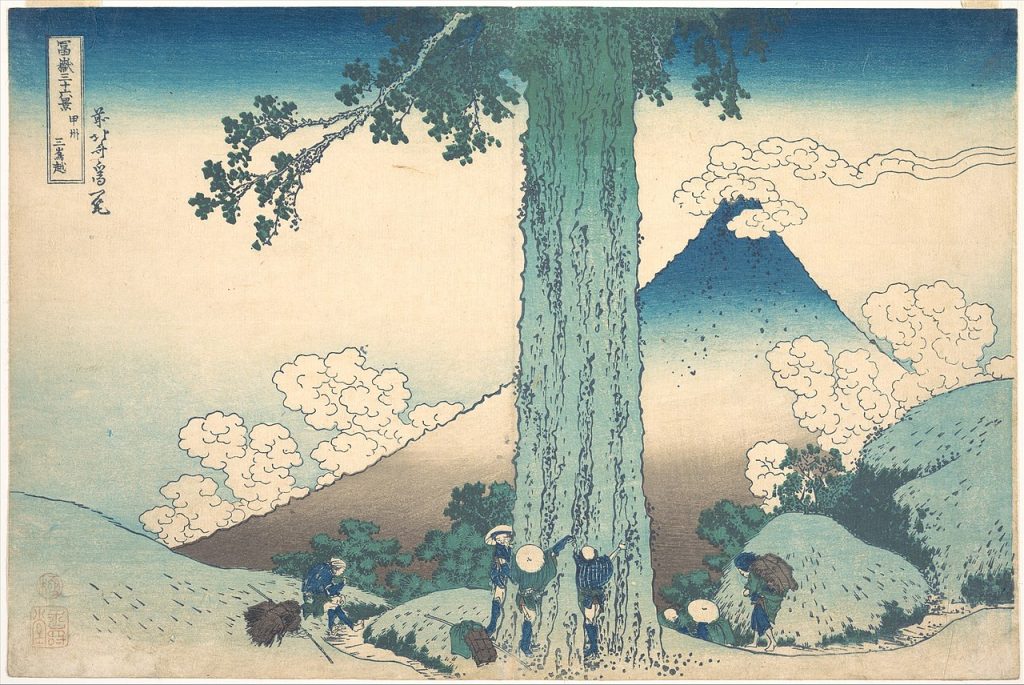

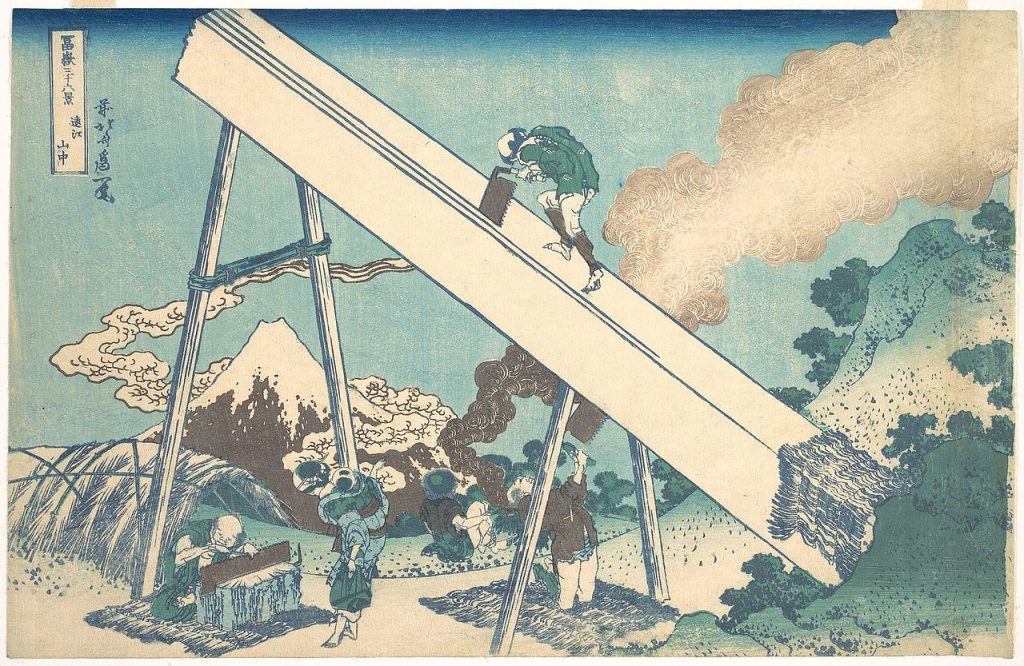

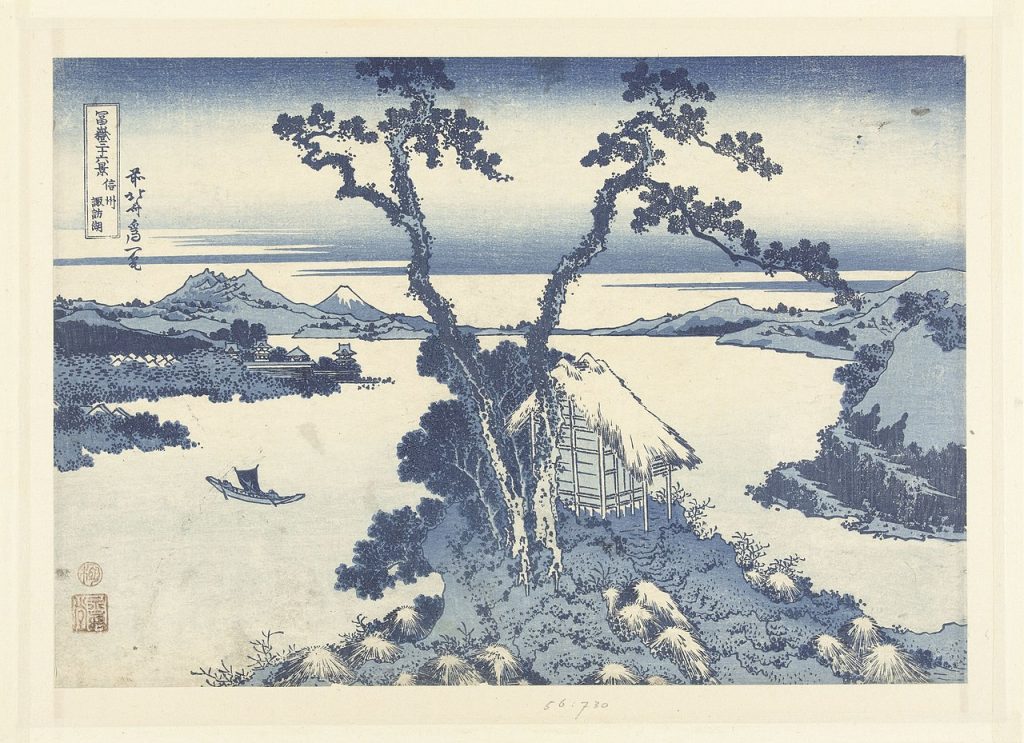

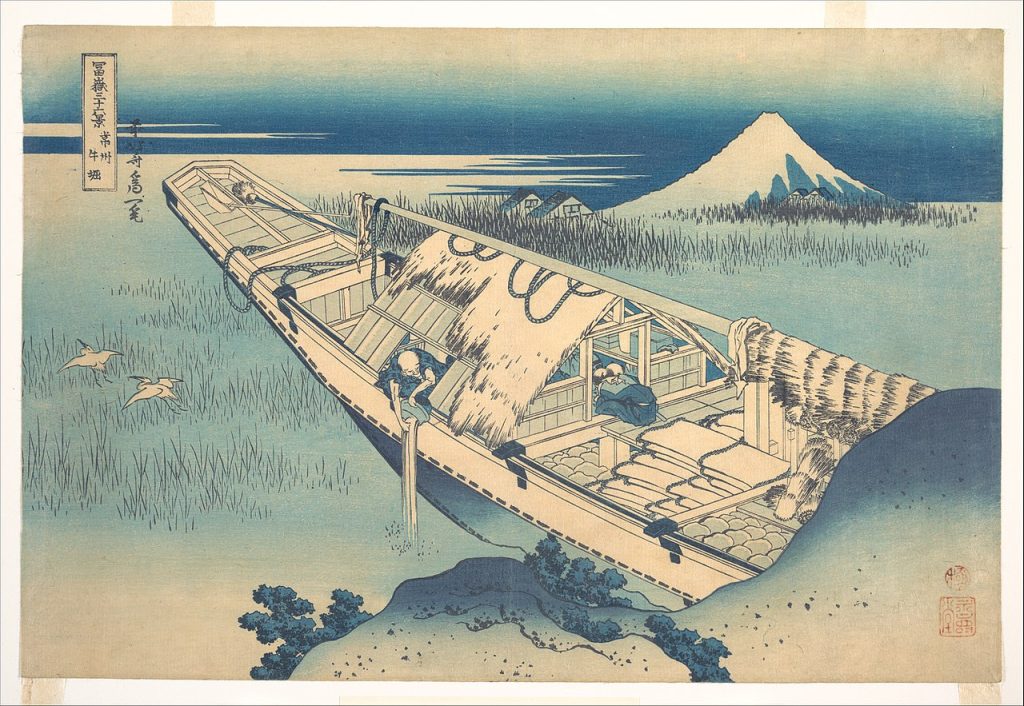

We took a holiday in Japan in November. Our first family trip to Japan – much awaited destination and much awaited vacation. Inspired by Hokusai’s Thirty-Six views of Mt. Fuji and my general curiosity and keenness to understand Japan through numbers, here are thirty -six short notes on Japan.

(All the numbers data is generally directional. Different sources sometimes show different numbers for the same parameter. Please do allow for margin of error and refer to the following only for broad brush understanding.)

The images are copied from Wikipedia.

All currency ($) referred is USD unless specified.

***

1. Population

Japan has a population of 124.5 million people. In 1800, Japan was 30 million people when the world was 1 billion people (fairly significant). In 1900, it was 44.3 million people, when the world population was around ~1.6 billion people. And in 1950, it was 83.2 million people, when the world population was 2.5 billion people. In 2010, it peaked at around 128.1 million people when the world population was 6.7 billion. Since then, the population in Japan has been declining. Japan’s fertility rate currently stands at 1.37.

On average there is a decline of 448k every year. At this rate, it is expected that by 2050, the population will perhaps drop to 105 million.

At the moment, it ranks number 12 in the world by population. The largest at the present times (Jan 2025) is India with 1.45 billion, and next China with 1.42 billion. In terms of developed countries, US is the third largest globally with 345 million people, followed by Indonesia with 283 million people and Pakistan’s 251 million people. Next is the largest African country in terms of population, Nigeria with 232 million people, followed by Brazil’s 212 million people. Bangladesh (174 million people), Russia (145 million people), Ethiopia (132 million people), Mexico (130 million people) are next few before Japan’s 124.5 million people. (Data from different sources – numbers for directional sense only). For reference, the population of the entire globe is close to ~8.2 billion people.

It is interesting to note the number of people residing in Asia – esp South Asia (~2b) and SE Asia (~700m) apart from China(1.4b). Then again, one understands where US is given both its size of population and the development levels of that mass of people. Next to that size in developed nations is only Japan, and that is a different story. If you were wondering, in terms of Europe, Germany is the largest with 85 million people, followed by UK’s 69 million, France’s 66 million and Italy’s 59 million.

2. Land Size & Population Density

Japan is 378k square kilometres spread across ~14,000 islands, with 4 main ones (Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku), others being called remote islands. 81% of the population lives on Honshu, where Mt. Fuji is also located. (Interestingly, until a few years ago, the number of islands was supposed to be ~7,000, but now the count has moved up, although area remains unchanged).

Japan is the 4th largest island country in the world. The largest being Indonesia (over 5 times size – 2 million sq km, over 2 times population). Next is Madagascar and third largest is Papua New Guinea.

In terms of a comparison with the world’s largest countries area-wise, Russia has around 17 million square kms. Next, Canada, China and US each has somewhere between 9-10 million square kms.

With population density of 326 per square kilometre, Japan is the 12th densest country (in countries over 10 million people). And 4th densest if one were to look at population over 100 million. (Bangladesh, India, Philippines would be the top 3).

Just as an extreme, I would like to compare it to New Zealand, another island nation and a developed country loved by tourists. Where NZ has 270k square kms (70% of Japan’s size), it has only 5 million people in that area to Japan’s 124.5 million. The other comparison is perhaps with UK. With 245k sq km, it is smaller than Japan (65% of Japan), and has ~68 million people living on it (or close to half that of Japan).

3. Urban-Rural understanding

Migration to towns and cities is a very recent human phenomenon – mostly unfolding over the last 200 years. It is estimated that in 1800, <3% of the world’s population lived in cities. If one were to perhaps consider this that in 1960, roughly only a third of the world population lived in cities, the starkness of this phenomena – of how the modern human lives becomes apparent. 2007 marked the year when total urban population surpassed total rural population globally. It is now ~56%, or c. 4.4 billion people live in cities. In the developed world, this number is close to 80%.

“Urbanisation is an unavoidable consequence of modernisation.” Over 80% of global GDP is now generated in cities.

For Japan, 93% of Japan population is urban population. In contrast, 82% of the US is urbanised, 84.4% of the UK is urbanised, 81.4% of South Korea is urbanised. China is 66% in urban areas at the moment. Japan is one of the world’s largest countries that way in terms of proportion of urbanity.

Japan started to urbanize in 1920s, and was over 50% urbanised in 1970. Between 1920 and 1980, the urban population increased from 10 million to 89 million, from 18% to 76% of the population. So perhaps here too, it is the last fifty years that have seen this growth to over 90%.

As a comparable number, Japan was 50% urbanised in 1970, North America was over 50% urban in 1925. And Europe was over 50% urban by 1950. The other country to consider is South Korea (51.7m pop), which was 28% urbanised in 1960, and was over 81% by 2018.

Although one staggering indicator here is Brazil with 87% urban population. For a developing and relatively large nation (212 million pop), it has a high proportion of urban population. Since 1970s, Brazil has consolidated itself as an urban country. Argentina, another South American developing country has 92.5% urbanisation.

A little point of reflection:

“Advancements in agricultural practices and technology then coincided with the beginning of the industrial revolution in Europe in the late 19th century, which resulted in waves of urbanization to meet the demands of emerging manufacturing industries. This trend was replicated across the rest of the world as it industrialized over the following two centuries, and the most significant increase coincided with the industrialization of the most populous countries in Asia. In more developed economies, urbanization remains high even as economies de-industrialize, due to a variety of factors such as housing availability, labor demands in service industries, and social trends.

Urbanization in the future represents an important determinant of the world in the future. The reason is that urbanization means the transition from agrarian society, characterized by the cultivation of land and self-supporting, to industrial society, characterized by dominant people living in urban sector with employment in non-agrarian work sectors. Urbanization, accompanied by modernization of labor pattern and lifestyles, has a significant impact on human behavior and consciousness, and results in the transition to an extremely urbanized society never before experienced in the past.”

4. Cities

Not just urbanised, Japan’s population is concentrated in a few cities.

“The population of the wider metropolitan area in which Tokyo is situated is approximately 40 million people. The continuously urbanised Tokyo commuter zone has about 35 million people. The official Tokyo local government area (i.e. the prefecture, or TMG) has 14 million people and the ’23 Special Wards’ of Tokyo contain just under 10 million people.”

So just under a third of the country resides in Tokyo. And yet, when one travels through Japan on trains, at least wherever the tracks go, they seem to be generally surrounded by houses.

Tokyo can be considered one of the largest cities in the world, or perhaps the largest. But considered that way, according to encyclopaedia Britannica, Guangzhou China has a population of 70 million, larger than most (except 20 countries) in the world. As a comparison, New York is 22 million people.

Not many developed countries in the world are centralised like this in one or two cities. But there are countries like Mongolia, Paraguay, Uruguay, Liberia and Armenia where more than half of the country’s urban population live in its largest city.

Osaka, another Japanese city has over 17.7 million people in its urban network.

One has to keep in mind the following comment from Britannica on cities while considering these numbers

“But, what defines a city? When you are comparing developments with tens of millions of people located in countries across the globe, a unified definition is tricky—one needs to consider a variety of population groupings, including urban populations, consolidated urban areas, agglomerations, and conglomerations. However, all these groupings have one thing in common: they feature a central city surrounded by contiguous settlements of people.”

By 2050, close to 7 billion people in the world are expected to live in urban areas. (Of a total expected population of 9.8 billion).

5. Age distribution

One of the often-discussed features of Japan is its ageing population. 30% of people are 65 years or older implying 36.65 million are seniors. For context, in 1960, this was 5.8% of the total population or 5.5 million then. Along with becoming highly urban, Japan has also aged.

“Demographers issued their first warnings in the 1970s and a national debate erupted in 1990 with the “1.57 shock,” when the country’s birth rate fell to its lowest level in recorded history. (The rate has since gone lower.)”

The current birth rate in Japan is ~1.26 births per woman. For the world, this is 2.3.

The median age of Japan is 49.5 years old. In certain ways, this is one of the highest in the world.

For the entire world, around 10.12% of the population is aged 65 and over. The world median age is 30.6 years. In 1974, the global population over 65 was 5.5%, the proportion doubling to over 10% at the moment and expecting to double again by 2074.

In terms of people 65 years or older, China currently has over 200 million people in that age group, India, some 85 million people, and the US, around 58 million people. What makes Japan different is the distribution. Amongst the larger countries of the world, it has the highest proportion of seniors, or perhaps it is the “grayest”. It is one of the effects of its declining population as well.

Although the overall population in Japan is declining, yet, interestingly, the working population in Japan is increasing. Both – female participation and older people participation in the work force is increasing. At the moment, 68.14 million people are employed in Japan (which is the highest ever), 37.06 million men and 31.08 million women. “Employment of people aged 65 and above has doubled from about 4.5 million in 1995 to more than 9 million today.”

And compared to early nineties where ~57% working age female were participating in labour force, now close to 75% do. This change of women participation in workforce is bringing about other changes too in terms of family attitudes and responsibilities.

“Global demographic trends marked by transitions to low levels of fertility, smaller families and ageing populations, as well as increasing urbanization and international migration, are changing the household contexts in which people live.”

“Japanese family structures have been influenced by Confucian ideas of filial piety and defined hierarchical social relationships over the centuries.” And yet, Japan has over 55.8 million households. Massive demographic changes have significantly affected the traditional family structures.

The average household size is 2.25 in Japan. This is 2.6 in the US, 2.98 in China, 4.44 in India. Some of the sub-Saharan and West Asian countries have quite large households (6-8 people on average). But most of the developed world is in the 2 -3 range.

6. GDP

Japan’s GDP in 2024 is estimated at $4.1 trillion. This makes it the world’s fourth largest economy. Until 2022, Japan used to be the third largest economy, ahead of Germany.

In 2012, Japan reported a $6.2 trillion in GDP. At the moment, Germany is $4.6 trillion. But of a completely different magnitude is the world’s largest economy, USA at $28.8 trillion, followed by China at $18.5 trillion. India is fifth largest, at $3.9 trillion. The entire global GDP is around $110 trillion implying USA contributing close to a quarter of global GDP with ~4.1% of the world’s population. This is where USA is perhaps leagues apart from any other country in the world.

In terms of per capita GDP, Japan stands at $46,300 per capita (or $53.06k at PPP). For comparison, USA per capita GDP is at around $86,600. China at around $12,970 ($26.31k at PPP).

In terms of growth, after the Second World War (WWII), Japan saw growth of over 10.1% on average p.a. during the 1960s, then 5.2% in 1970s and 4.6% in 1980s. The period from 1955-1973 is often referred to as Japanese Economic Miracle for the unprecedented levels of growth. For a country not very rich in resources, this was quite a high growth.

But since 1991, what is now called ‘Lost Decade’ began in Japan with the significant fall of asset prices. The economy then grew at an average of 1.4% for a while. It took Japan around 12 years to reach back the GDP levels of late 1995. After this decades-long stagnation of sorts, even now, although the economy is growing, other demographic features make sustaining the growth difficult. Over the last 10 years, the CAGR is 0.8%, but over the last 3 years it is 1.9%.

At the moment, one of the key priorities for Japan is to find the best way forward with its current demographic mix, to harness this high dependency ratio economy back to growth through this whole new proportion of seniors in a country that the world has never seen before. It is often discussed and debated in the local politics and media.

“The country shouldn’t attempt to compensate for its dwindling population with revitalized productivity. Economist Yumiko Murakami explored this idea in her notion of a “silver economy.” For her, there is limitless potential when the most advanced technologies are married to innovative ideas to address the new demands of an aging society. Not only will a growing elderly cohort demand new products and services, but it will also require the redesign of social infrastructure, which ranges from transportation to health to education. At the same time, labor shortages will allow Japan to adopt technological fixes to productivity problems without having to fight opposition from labor like other countries with younger populations. Like Kushida, she concluded that “potential markets for these types of innovative products and services are vast and commercially attractive. Japan is well-positioned to enjoy a first-mover advantage in this regard.”

Much of the rest of the world is slowly heading that way. In terms of largest economies, both Japan and US are wealthier countries. But China and India have not reached that threshold and yet will have a very big ageing population, although with better dependency rations. Still, how Japan addresses some of these areas will pave the path for rest of the ageing world as well.

7. Composition of GDP

For the economy of Japan, agriculture contributes 1% of the GDP, industrial ~29% and service sector, 70% to the GDP. This is similar to Germany in many ways. But if one looks at the US, agriculture contributes 5.6% and the services sector contributes ~75% to the GDP, while in China, the largest manufacturing economy in the world, the industrial sector accounts for 40.1% of the economy with agriculture also contributing 6.9%. Amongst the larger economies, perhaps it is only India with 17.4% contribution from agriculture, and yet, in terms of dollar value, China is the largest in terms of agricultural output ($843 billion against India’s $391 billion).

Japan contributes over $1 trillion to manufacturing. It has the third largest manufacturing output in the world after China’s $2 trillion, and US’s $1.8 trillion. Perhaps worth mentioning here that Japan has been either the second or third largest manufacturer globally since 1970s, with China coming up as a large manufacturer only in the last couple of decades. In the 1970s, Russia used to be one of the larger manufacturers. (Note – ‘Industry sector’ in GDP generally includes mining, manufacturing, energy production, and construction.)

For Japan, in the 1950s, agriculture contributed ~20% of the GDP, but by late eighties, this was close to 3%.

In terms of employment, 25% of the working population is in manufacturing, 72% in services and 3% in agriculture.

8. Exports and Imports

Japan is the fifth largest exporter and importer in the world.

In 2023, Japan imported ~$ 1 trillion worth of goods and services and exported around $920 billion worth of goods and services. Traditionally it has had a large trading surplus, but recently this seems to have shifted.

To compare, the world’s largest exporter is China with exports of $3.51 trillion and the world’s largest importer is United States with $3.81 trillion imported. United States is also the world’s second largest exporter.

For Japan, the largest import categories are energy related (crude, petrol, gas, coal – over $200 billion), integrated circuits ($28.9 billion), and broadcasting equipment ($20.3 billion). The largest export categories were cars ($89 billion), machinery having individual functions ($38.5 billion), integrated circuits ($36.9 billion) which as a category is also one of its largest imports. Also incidentally, automobiles are world’s largest traded goods ($1.35 trillion, with Germany being the largest exporter). Refined Petroleum is next at $825 billion.

“Japan is a country lacking natural resources, and hence has developed itself as a processing nation, importing raw material and exporting value added products.”

In 2022, Japan was the world’s biggest importer of other prepared meats ($3.02 billion – this is different from the main items of meat traded across the world), ethers ($2.28 billion) and processed tobacco ($1.75 billion). And it was the world’s biggest exporter of machinery with individual functions ($38.5 billion) and hot-rolled iron ($11.2 billion).

In terms of trading partners, the key countries where most goods exports go from Japan are United States ($137 billion), China ($135 billion), South Korea ($50.8 billion). Japan imports most from China ($178 billion), Australia ($80 billion), US ($80 billion).

Perhaps here, a bit on Japan’s investments around the world too.

Japan is one of the largest Foreign Direct Investor around the world. In 2023, it was the second largest with outgoing investments of $184 billion. Total global FDI was $1.55 trillion in 2023 (flow). US being the largest in the world with $404 trillion FDI investments. China, third largest with $148 trillion.

Japan’s position of holdings is sixth largest in the world, with holdings of over $2 trillion (stock). Most of these FDI holdings are in the US, followed by Netherlands and UK.

Total world outward FDI stock is $44.3 trillion (2023). Some of the largest holdings are with US ($9.4 trillion, although inward of $12.8 trillion), Netherlands ($3.3 trillion), China ($2.9 trillion, China inward is $3.6 trillion), Canada ($2.7 trillion), Germany ($2.1 trillion) and Japan with $2.1 trillion.

The interesting thing about Japan is inward FDI stock is only $225 billion compared to the inward FDI numbers of some of these other large economies. “The major investing countries in terms of FDI stock are the U.S. (22.3%), the UK (16.7%), Singapore (10.4%), the Netherlands (7.3%), France (7%), and Hong Kong (5.7% – data Japan External Trade Organization). Investments are mainly oriented towards finance and insurance, transportation equipment production, electric machinery, communication, and chemicals and pharmaceuticals.”

9. Agriculture

Agriculture in Japan contributes ~1% to national GDP. Most of Japan is mountainous, and only about 12% of the land in the country is appropriate for farming. In terms of agricultural food-sufficiency, although many countries in the world are self-sufficient and exporters, only a few developed countries are self-sufficient (such as Australia, US, France). Japan is around 38% self-sufficient on calorie basis and 58% on production value basis.

This makes Japan the second largest agricultural product importer in the world. (China is the largest importer). And even though it needs to import agriculture goods, Japan is self-sufficient in rice production. It is the 12th largest producer of rice in the world, largest being India and China (both order of magnitude higher than rest). Rice is the most important crop in Japan, and other crops include soybean, wheat, barley.

Over the recent years, wheat consumption has gone up in Japan with changing food habits.

“The United States is the largest supplier of food and agricultural products to Japan, with the largest share of imports, followed by the European Union, China, Australia, and Thailand. Japan is the largest export market for U.S. beef and pork, valued at nearly $5 billion combined, and the second largest market for U.S. corn, valued at $3.3 billion.

Japan’s largest grain import from the US is maize, with about 15 million tonnes of US maize imported in 2018.”

In terms of total agricultural output:

“The breakdown of the value of agricultural output by sector: Livestock led the way at ¥3.5 trillion (38.5%), followed by vegetables at ¥2.2 trillion (24.8%), rice at ¥1.4 trillion (15.5%), and fruit at ¥0.9 trillion (10.3%).”

Agriculture was one of the key employers until WWII (50% of workforce), but over the time since, with rapid industrialisation, now agriculture employs around 2 million people (or 3% of workforce). Perhaps a stark figure here is the decline in number of farmers over the decades (from 10 million in 1970 to 2.6 million in 2010), and the increasing proportion of farmers over 65 years of age (from 18% in 1970 to over 61% in 2010). Japan has the fastest-aging agricultural labor force. There has been a major change since WWII because of the competition of labour from industrial sector.

“Family farming still accounts for over 90% of total farming enterprises. But Japan’s farming population has been declining, accounting for just 1.1% (1.36 million) of the total population in 2020. While family farming remains a dominant form of agriculture in Japan, it is no longer the social foundation of the country.”

10. Farm sizes

One of the interesting indicators for Japan is that amongst the developed countries, it has one of the lowest average farm sizes. Where countries like US and Canada have average farm size of over 100 hectares, UK, ~71 hectares, France & Germany, somewhere between 40-45 hectares, Japan has an average farm size of 1.2 hectares.

Italy, another relatively developed country has average agriculture hectare size of 7.57.

India also relies on small farms, average being 1.33 hectares, but India has a large population relying on agriculture as primary source of work and revenue. Amongst developed countries, Japan presents a unique picture.

Perhaps the starkness of how two countries differ – for Japan, the number of farms has fallen from 2 million to 1.1 million, still it is not very different from US, the third largest global producer of agricultural products (after China and India). The US also has around 1.9 million farms. But the area under cultivation is degrees of magnitude higher since the average farm in the US is 187 hectares against Japan’s 1.2 hectares. (Some data sources now put it closer to 3 hectares).

Part of the reason is Farmland Reform after WWII where farmers were permitted to own farmland up to one hectare and were also prohibited from renting additional farmland resulting in many tiny holdings in Japan. Though such restrictions do not exist, still perhaps it has had a long term effect on the ways in which farmers value farmland.

“When labor is abundant relative to land in the early stage of economic development, labor-intensive methods of cultivation are socially efficient. In such cultivation systems, no major indivisible inputs are used and, hence, there is no major source of scale economies. Roughly speaking, a farm of 1–2 hectares can be managed efficiently by family labor consisting of a few workers. Beyond that scale, hired labor must be employed. However, the monitoring cost of hired labor arises, which increases more than proportionally with the cultivation size (Feder 1985; Otsuka, Chuma, and Hayami 1992; Hayami and Otsuka 1993). This explains why the family farm dominates in agriculture in most countries in the world (Berry and Cline 1979; Eastwood, Lipton, and Newell 2010). Thus, the optimum farm size in low-wage economies is bound to be small because of the limited availability of family labor and the costly substitution of capital for labor. This situation was predominant in East Asia (that is, Northeast and Southeast Asia), which justifies the dominance of relatively small operational sizes.

Now, even though the East Asian nations are moving towards higher average farm size, South Asia farm sizes continue to stay at similar small sizes as past. It is perhaps a reflection of primary dependence of a family on a farm, rather than farming as an enterprise. And perhaps it is a function of real wages in the economy:

“In South Asia, the land-labor ratio has not increased in the period from 1961 to 2014. In Pakistan, India, and Nepal, declines in the land-labor ratio were observed in recent years (India shows a downward trend). In contrast, machine use per worker has been increasing over time in all countries except Pakistan and Nepal in recent years. At the stage where machine use per worker increased while land-labor ratio staying relatively constant, as seen in South Asia and many Southeast Asian countries, the process is driven by small-scale machines that do not require large operational size. However, when real wages start rising fast, the need to introduce large-scale machines coupled with an effort to increase operational size (farm size) becomes much stronger.”

11. Income-Doubling Plan

Consider the following:

“After World War II, about 6 million people returned from overseas to devastated national land. Furthermore, due to a poor rice crop in 1945, food rations could not be distributed in large cities, and people suffered from starvation.The government initiated an emergency reclamation project in 1945 for an urgent implementation of food production increase and unemployment measures.

Japan recovered her sovereign power in 1951 with the conclusion of the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

In 1956, the government declared that the country “no longer be termed postwar” in economic white papers, and the basic policy of Japan was to become a big economic power with increased national incomes.”

Since the post-war years, Japan has set up many economic plans, over fifteen, but one of the most interesting things (compared to such other plans elsewhere) these plans ended up delivering much more than initially planned.

One such plan was Income-Doubling Plan. After the Self-Support plan of 1955 which aimed for restoring equilibrium in balance of payment situation and aimed for 5% growth rate and delivering all of the plan in two years against five, this Income-Doubling Plan plan adopted in 1960 shifted the drivers of the Japanese economy. The aim was to double the national income within ten years or realise 7-8% p.a. growth, through five major policy objectives:

“The five elements in the plan are (1) expanding social overhead capital, such as roads, harbors, factory sites, and water facilities, which tend to lag behind direct productive capital, (2) strengthening the industrial structure by increasing the relative importance of the sectors where labor is more productive, such as the heavy and chemical industries, as well as by raising the productivity of individual enterprises, (3) promoting foreign trade and international economic cooperation, (4) improving the quality of labor and promoting science and technology, and (5) improving the living standards of the low-income group and increasing over-all social welfare.”

Like other such economic plans drawn by Japan, it delivered more than planned. Japan’s annual growth averaged more than 10% during the period and the economy doubled in size in less than seven years. There was ambitious investing in urban infrastructure. During this period was the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and related infrastructure spends, Shinkansen (bullet train), Expressway and underground metro system. High quality Japanese products began to be exported across the world. Social safety nets were created.

The plan has been a case study for many developing countries.

12. Government Debt

In proportion to its GDP, Japan has the highest outstanding Government debt amongst all the large economies of the world (~250% of GDP). Amongst all other countries too, perhaps the only country with higher proportionate debt is Sudan and at some point, Lebanon.

The total gross government debt as of April 2023 was $9.4 trillion. It touched a high of $12.6 trillion in 2012. In terms of actual absolute numbers, perhaps USA has the largest national debt ($32 trillion in 2023, at 120% of the country’s GDP). USA also makes up a third of the global government debt outstanding. Perhaps the larger developed economies in the world face this problem of high debts with low growth rates further resulting in higher debts due to deficit funding. 68% of the global debt is held by developed countries. (Which is a strange long term unsustainable path development has taken).

China also has a high climbing gross debt, at $14.6 trillion. Still in terms of percentage of its GDP, it is at 83.6%.

Anyhow, the numbers in Japan are highest in proportion of its economy. The reasons lie in the ‘lost decades’ since the asset price bubble collapse in 1991. Before this (and after the temporary highs of world war period, Japan’s debt outstanding in 1989 was at ~70%).

“Japan’s asset price bubble collapse in 1991 led to a prolonged period of economic stagnation described as the ‘Lost Decades’, with GDP falling significantly in real terms through the 1990s. In response, the Bank of Japan set out in the early 2000s to encourage economic growth through the non-traditional policy of quantitative easing. By 2013, Japanese public debt exceeded one quadrillion yen (US$10.46 trillion), which was about twice the country’s annual gross domestic product at that time, and already the largest debt ratio of any nation.

Until the 1980s, the gap between tax revenues and expenditures was relatively small, so that the amount of JGBs issued for each fiscal year never exceeded ¥15 trillion. However, with the collapse of the bubble economy and prolonged economic stagnation, the balance of payments deteriorated as a result of repeated fiscal stimulus packages and tax cut policies. The outstanding amount of issued government bonds has since been increasingly annually and is predicted to reach ¥1.1 quadrillion by the end of fiscal 2024.”

..

“During the Japanese asset price bubble of the late 1980s, revenues were high due to prosperous conditions, Japanese stocks profited, and the amount of national bonds issued was modest. With the breakdown of the economic bubble came a decrease in annual revenue. As a result, the amount of national bonds issued increased quickly. Most of the national bonds had a fixed interest rate, so the debt to GDP ratio increased as a consequence of the decrease in nominal GDP growth due to deflation.”

..

“The growth of annual revenue was slowed down by the prolonged depression. Consequently, the governments started issuing additional national bonds to cover the interest payments. This national bond is called renewal national bond. As a result of issuing these bonds, the debt is not actually repaid, and the amount of bonds issued continued to grow. Japan has continued to issue bonds to cover the debt since the asset price bubble collapse.”

On average 40 trillion yen of bonds issued every year for last 25 years. (Which is c. $300-400 billion depending on exchange calculations)

13. Savings & Wealth

After WWII, Japan had one of the highest household saving rates in the world. It showed an upward trend until mid-1970s when it peaked at 23.2% and since has been showing a downward trend – by 2004, it was 2.6% and by 2022, around 3.4% (except during Covid period). The decline is often attributed to the decline in savings of elderly households.

“However, it is likely that other factors such as the unavailability of consumer credit, the unavailability of social safety nets, high rates of economic (income) growth, tax breaks for saving, saving promotion policies, and high and rising land and housing prices are also partial explanations for why Japan’s aggregate household saving rate was so high during the 1961-86 period and why it declined so much subsequently.”

This high household saving rate is credited for being one of the primary causes of Japan’s double-digit economic growth during the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s (the so-called “Japanese economic miracle”).

According to one data source, the total wealth in the world is estimated at $454 trillion. In terms of the large countries, $139.9 trillion of this wealth is in US, $84.5 trillion in China, and Japan is perhaps the third largest at $22.6 trillion.

In terms of asset mix in Japan, although similar to other developed countries, a large part is financial assets (63.2%, similar to North America’s 62.8%, although different from Aus/NZ’s 40% and Europe’s 50%, remaining being real estate). “This is surprising as real estate assets – usually the owner-occupied house – are generally regarded as the largest asset item on a household‘s balance sheet.”

Still, in terms of financial assets, what stands out for Japan is that relatively few people own stocks (over the last ten years, equities have gone up from ~10% of household assets to ~14.2% of household assets, compared to ~40.5% of US household assets). Many keep their savings in bank accounts. This is a very different picture compared to the rest of the developed world, many developed world households withdrew deposits from banks to the exception of Japanese households (and South Korean and German).

“As of March 2024, currency and deposits accounted for the largest share of financial assets held by households in Japan with 50.9%. Currency and deposits were followed by insurance, pension, and standardized guarantees with about 24.6%. Household financial assets in Japan amounted to over two quadrillion Japanese yen in 2024.”

..

“Savings behavior is a decisive factor for asset growth. There are basically two sources of growth in financial assets: savings efforts and price increases (increase in value). For example, over the last 20 years, increases in the value of portfolios in the US – with its strong savings bias towards capital markets – have contributed an average of 62.4% to annual growth; in Western Europe, this figure is 34.2% (in Germany, growth over the long term is driven almost exclusively by savings efforts). This significant difference certainly contributes to the Atlantic divide in long-term growth in financial assets: While financial assets in Western Europe have doubled in the last two decades (+104%), the increase in the US is a whopping +178%, also bolstered by more favorable market developments.”

In terms of time trends, North America (for the last 20 years) has held around half of global financial assets. During the last two decades, China’s share of global financial assets grew from 2.6% to 14.1%, Japan’s share came down in relative terms.

“Over the course of this century, and particularly after the 2008 global financial crisis, financial wealth has grown at a faster rate than non-financial wealth.”

In terms of what form this wealth or global assets take, $380 trillion is real estate ($287 trillion residential, $51 trillion commercial and $41 trillion agricultural land), $130 trillion in debt securities, $99 trillion in equities and total gold ever mined of ~$12.2 trillion. For context, the global GDP is ~$100 trillion.

Of the total global real estate, China accounts for a quarter of the global real estate value ($88 trillion), followed by the US at 19% , and Japan next at $20 trillion. (To note that to compare wealth numbers with asset numbers, one has to adjust for financial liabilities as well).

There are several ways to consider global wealth. Another way to consider it is as done by McKinsey. This is contrasting to the usual way of looking at household assets and liabilities. Here, by drawing a global balance sheet, one looks at the real net worth of the globe, the ‘real’ assets, cancelling out for all financial ownings and owed.

“At a functional level, the global balance sheet has three components that interlock: the real economy balance sheet, the financial balance sheet, and the financial sector balance sheet. Each amounts to about $500 trillion, or the equivalent of about six times GDP.”

With their estimates (before cancelling out for liabilities), world’s total assets are $1,540 trillion. Around two-thirds of these are financial assets, which with around $1,000 trillion of financial liabilities are netted off. So the net-worth remaining is $500 trillion. (Similar to the other number on global wealth). Real Estate accounts for a third of the real assets.

“The real economy balance sheet has $520 trillion in real assets, such as machinery and equipment, infrastructure, buildings, natural resources, and intellectual property, or IP. These are mirrored on the liability side as net worth.”

Perhaps what is interesting in their way of seeing is that as a ratio of GDP, each of these components grew from about $150 trillion in 2000, or about 4 times GDP to about $500 trillion or about 6 times GDP in 2020.

“Before 2000, net worth growth largely tracked GDP growth at the global level, with occasional country divergences from the pattern, such as in the United States in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the run-up to the savings-and-loan crisis and in Japan during the asset bubble followed by a banking crisis in the early 1990s. Nearly all net worth growth from 2000 to 2020 occurred in the household sector as a result of growing equity and real estate valuations.”

Especially in advanced economies, the cause of this divergence of the link from GDP:

“In an economy increasingly propelled by intangible assets like software and other intellectual property, a glut of savings has struggled to find investments offering sufficient economic returns and lasting value to investors. These savings have found their way instead into real estate, which in 2020 accounted for two-thirds of net worth. Other fixed assets that can drive economic growth made up only about 20 percent the total. Moreover, asset values are now nearly 50 percent higher than the long-run average relative to income.”

The question it raises: “is it healthy for the economy that high house prices rather than investment in productive assets are the engine of growth, and that wealth is mostly built from price increases on existing wealth?”

(Perhaps here worth mentioning, that a large portion of this ‘wealth’ is consolidated with the top few. These numbers are just to place things in context – esp the picture of overall distribution across countries. The wealth numbers mean little in a lopsided world. (Half the world has less than $10k to their name). Here again, this is the enumerated world only. It is a very rough indicator esp given PPP differences. Only between the top few advanced economies is there some semblance of comparison. One of the things that has happened since 2000 is the general global expansion of middle classes. There is a lot of growth, but there is a lot yet to be done in terms of a minimum standard of living for a lot of people across the world.)

On that note, again, in advanced economies, Japan stands out.

Piketty’s main assertion is that the leading driver of increased inequality in the developed world is the accumulation of wealth by those who are already wealthy, driven by a rate of return on capital that consistently exceeds the rate of GDP growth. Japan, however, has lower levels of inequality than almost every other developed country. Indeed, though it has long been an industrial powerhouse, Japan is frequently called the world’s most successful communist country. Japan has a high income-tax rate for the rich (45%), and the inheritance tax rate recently was raised to 55%. This makes it difficult to accumulate capital over generations – a trend that Piketty cites as a significant driver of inequality. (From 2015)

In terms of inheritance tax around the world, Japan has the highest at 55%. In the US and UK, this is 40%, South Korea, 50% and France 45%. Many other developed countries do not have any or they have eliminated it as there is much debate on the net benefits of taxing inheritance. Even countries like Norway and Sweden, otherwise known for their less capitalistic policies.

14. Pension Funds

Government Pension Fund Japan is the largest pension fund in the world with total assets of $1.6 trillion. It has ranked top in the world since 2002. To put it in context, the top 300 pension funds in the world total $22.6 trillion, and the total pension assets across 22 major pension markets account to $55.7 trillion.

There are 11 other pension funds from Japan in the top 300 pension funds globally, 4 of them with over $100 billion in assets.

Although the world’s largest pension fund is from Japan, in terms of total pension assets held by a country, US is by far the largest with $35.6 trillion, followed by Japan with a total of $3.3 trillion, UK $3.2 trillion. Twenty years ago, these numbers were $10 trillion for US and $2.9 trillion for Japan, $1.2 trillion for UK. The growth in pension asset base is different in other countries.

Pension Funds can be Soverign Funds (like the Japan GPIF, there are 24 in top 300, managing 30% of total AUM), Public Sector Funds (generally for public sector workers, 128 in top 300, 40% of total AUM), Private Independent Funds (managing pension plans for different employers, 68 in top 300, 16% of total AUM) or Corporate Funds (80 in top 300, $2.9 trillion or 13% of total AUM). In terms of ratio to GDP or relative to the size of economy, Japan’s public pension reserve fund (PAYG schemes) is one of the highest in the world (38% of GDP, only South Korea has higher at 46% of GDP). The US has a larger public pension reserve fund in dollar terms ($2.6 trillion in reserves, 9.7% of GDP), but as a proportion of its total pension assets, it is relatively insignificant.

Currently most of the pension assets in Japan are held in bonds (56%), 25% in equity. Compared to this, the investment strategy in the US is 46% equity, 34% bonds. And though for US these equities are mostly domestic (~70%), for Japan, only ~30% are invested in domestic stocks.

And still, Government Pension Fund Japan was until recently the largest investor in the equity markets in Japan. (At the moment, Bank of Japan is the largest equity investor in Japan with $470 billion in Japanese equity or ¬8% of total Japanese Stock Market) (personally, I consider this a point to further explore and assess – this relationship of institutional money with equity – the liquidity and consolidation of world markets, the connectivity). “It is unusual for the central bank to pour more money into the stock market than the national pension fund.”

In terms of the kind of plans, Japan has primarily Defined-Benefit (DB) plan (95%) against, say the Defined-Contribution (DC) market (88%) of Australia, another large pension asset country ($2.4 trillion) esp relative to its GDP. The US is also ~67% DC market. Canada is 43% DC. UK (81%) and Netherlands(95%) are DB markets similar to Japan.

“As the names imply, a defined-benefit plan—also commonly known as a traditional pension plan—provides a specified payment amount in retirement. A defined-contribution plan allows employees to contribute and invest in funds and other securities over time to save for retirement. These key differences determine which party—the employer or employee—bears the investment risks and affect the cost of administration for each plan.”

Globally, the long-term trend has been a shift away from defined-benefit plans given the higher inherent risks for employers (they need to cover for any funding shortfall to meet the defined benefits), and the move to DC makes the contributions more predictable. Hence, in countries where the pension is largely public, private or corporate, there is a slow move to defined-benefit plans.

At the moment, DB funds account for ~60% of the disclosed AUM of global top 300 pension funds.

15. Market Capitalization

The market capitalization of the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in Japan as of Dec 2024 was $6.475 trillion. The Tokyo Stock Exchange is one of the largest in Asia in terms of volume. It is managed by JPX (Japanese Exchange Group). The TSE has three market segments: the Prime Market (bulk of the market cap, $6.24 trillion, across 1640 companies), the Standard Market, and the Growth Market.

Founded in 1878, TSE is the 4th largest exchange in the world. The top two American exchanges are significantly larger than rest of the world. NYSE ~$30 trillion market cap, NASDAQ $28 trillion, followed by Shanghai Stock Exchange $7.2 trillion, JSE is fourth largest at the moment with $6.2 trillion.

And yet, just to put things in context, here is a little snippet of its history: “In early 1989, by market cap, Japan accounted for 45% of the global stock market, followed by the U.S. at 33% and the U.K. at 9%.” As the author there puts it, it is an incredible shift of global fortunes in 30-35 years.

3,800 companies are traded on the exchange currently. (This number was 1389 in 1978) . The largest company traded on the exchange is Toyota with $232 billion market cap and revenue of $312 billion. It is 45th largest company in the world by market cap. By comparison, Apple, the largest company in the world by market cap has $3.56 trillion market cap, and revenue of $391 billion. Walmart is the world’s largest company by revenue of $665 billion.

Other top few companies are Mitsubishi UFJ Financial ($141 billion market cap), Sony ($132.41 billion market cap), Hitachi ($118 billion). Perhaps to note here that there are 44 companies on TSE which grew over 10x in 10 years to 2022. The largest growth was in Sony which grew 12.4x during this period.

Before the asset bubble burst of 1991:

“In 1989, of the world’s top 50 companies by market capitalization, 32 were Japanese; by 2018, only one such company (Toyota) remains in the top 50.”

The Tokyo Stock Exchange’s benchmark index is the Nikkei 225. It fell significantly during the lost decades, but a few years ago, it climbed back to 1991 levels, and as of March 2024, reached a 34 year high of 40,000.

While we were travelling in Japan, Yomiuri Shimbun (the largest newspaper in the world by circulation), announced a new stock index in November 2024. It will be called Yomiuri 333 and will have 333 constituent companies. It will be launched in March 2025. It plans to equally weigh each stock in calculating the value unlike some of the other indices which are capitalization weighted (Tokyo Stock Exchange owned Topix and 198 constituent MSCI Japan Index) or price-weighted Nikkei 225 (launched by the world’s largest financial newspaper – The Nihon Keizai Shimbun or Nikkei. Other Price-weighted examples are Dow Jones Industrial Average.

The other new development which signifies Japan’s keenneess to open itself to foreign investment, is the requirement for English reporting from April 2025:

“To attract more foreign investment, all companies listed in the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Prime market — 1,600 of them in total — will need to release quarterly financial statements and other key information simultaneously in English and Japanese from April.”

At the moment, only 8% of Prime market companies provide full English-language versions.

16. Banking Sector in Japan

Japan banking sector has an asset base of $17 trillion. There are around 200 banks in Japan, with five major city banks. The Bank of Japan is the banker of last resort in Japan and controls the money supply.

There are large number of banks in Japan – five large city banks and over 100 regional banks.

The largest bank in Japan is Misubishi UFJ (or MUFJ), with total assets of $2.9 trillion. It is the 9th largest bank in the world. (Largest is ICBC China with $6.3 trillion in assets). Top 4 are banks from China. The second largest Japanese bank is Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group with total assets of $2 trillion. It is 13th largest in the world. Mizhuo, third largest in Japan is 17th largest in the world, with $1.9 billion total assets. The largest US bank JP Morgan Chase is fifth largest in the world with $3.8 trillion total assets.

Like some other countries in the world, the postal system in Japan also operates a banking system. With its reach of 24k branches, it is fourth largest financial institution in Japan with $1.7 trillion in assets. The US had a postal banking system from 1911 to 1967. In China, France and Japan, postal systems are full service banks. The total number of bank branches in Japan is 13.6k and Japan post has around 24k branches. For a large part of its history, Japan Post was government owned, but in 2005, a privatisation program for Japan Post began, and now government holds less than 50%.

In Japan, banking system has consolidated dramatically since 1990s. Some of these M&A figure in the largest M&As in the world. For instance, in 1989, Mitsui Bank acquired Taiyo Kobe Bank for $22.8 billion, in the second largest M&A of eighties. In 1999, Sumitomo Bank acquires Sakura bank for $45.5 billion in the fifteenth largest M&A of 1990s. In the same year, Fuji Bank acquired Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank and Industrial Bank of Japan for $40.1 billion. In 1995, Mitsubishi Bank acquired The Bank of Tokyo for $33.8 billion.

“For almost two decades, Japanese banks have operated in an ultralow interest rate environment and struggled with low profitability, forcing them to cut cost and seek business opportunities in overseas markets. Regional banks, of which there are over 100, have been particularly affected by Japan’s demographic change and declining economic activity in rural areas.”

Perhaps here a little note about mortgages in Japan. Since mid-nineties, Japan has had near-zero interest rates. Earlier in 2024, Bank of Japan raised the interest rates for the first time in almost two decades, from -0.1% to a range of 0 to 0.1%. (For context, before the bubble burst, the Japanese interest rates were around 6% in 1990. Since then, rapid decline until mid nineties, and for the last couple of decades, it has been in the very close to 0 range, when not negative). This prolonged period of Japanese low/negative interest rates resulted in a rippling effect in the world as well leading to large holdings in yen carry trade, with investors borrowing in Japan yen to take advantage of the low interest rates.

The total amount of outstanding housing loans to households in Japan was $987 billion in early 2024. This was 24.6% of the GDP. In the US, this number is ~$20.7 trillion.

17. A snapshot of IPOs, VC and PE in Japan

Japan has a relatively accessible IPO (Initial Public Offering) market with many small companies going in for listing early. Still, given the language barriers, most listings are local unlike some other developed country markets.

“The global IPO market recorded 1,215 deals, raking in US$121.2b in proceeds for 2024, falling slightly behind 2023 levels.”

~60% of this was accounted by US markets. The total was lower than 2023 given much slower IPO markets in China and HK.

Japan recorded $6.2 billion in capital raise in 2024 from ~84 IPOs. (In 2023, this was ~$3.7 billion). The largest IPO in 2024 was that of Tokyo Metro in October, which raised $2.3 billion. Tokyo Metro, which carries ~6.5 million passengers daily on average is one Tokyo’s two major subway operators. X-Ray technology company Rigaku closed a $863 million IPO. This was a Private Equity (PE) exit with Carlyle exiting the company. In December, Japanese chip maker Kioxia Holdings listed on Tokyo Stock Exchange, third largest for the year with $800 million. This was also PE exit, where Bain Capital exited part of the shareholding.

IPOs serve as fundraising means as well as an exit route for Venture Capital (VC) and Private Equity to list and exit shareholding in their portfolio. Compared to the US, where the ratio of IPO to M&A exit for VC backed companies is 3:7, it is 8:2 in Japan.

In 2024, public listings of private equity- (PE) and venture capital- (VC) backed portfolio companies generated 46% of total global IPO proceeds, highlighting their substantial contribution to global IPO activity and reinforcing the critical role of PE and VC firms in shaping the IPO landscape. Out of the 20 mega IPOs in 2024, 12 were PE-backed, a significant increase from the two listed last year. There were also 18 unicorn IPOs listed in 2024, half of which were launched by VC firms, up from just three in 2023.

VC in Japan is growing over the last decade. From very little amounts a decade ago, to now, $7 billion was invested in Venture Capital in Japan in 2023. As a comparison, total startup funding in the US was $160 billion in 2023. A large area for VC investments is AI. The other aspect about Japan VC scene is the significant presence of Corporate Venture Capital. Also Japanese VC investments are heavily weighted towards Seed Stage.

Another indicator that people track is the number of unicorns in a market. That is fairly limited in Japan: at the moment 7 to 9 comapred to ~660 in the US.

In terms of Private Equity in Japan, the aggregate deal value was $50.8 billion in 2023. (Total global deal volume was $474 billion in 2023). It is now becoming one of the larger markets in Asia Pacific. In 2023, Japan saw its largest PE transaction when Toshiba was taken private by Japanese Industrial Partners for $14 billion. The PE market in Japan has begun to rise recently from 2017. 8% of M&A was PE on average from 2014-2020 compared to 15% in US. Additionally, given the stage of the market, the kind of deals that dominate the market are buyouts.

One number that I came across which is quite interesting is the average EBITDA margin of Japanese companies (2018-20), it was 9.4% on TSE listed companies, compared to 15.1% on NYSE signalling the opportunity of margin improvement. Also “The average EBITDA multiple of the Nikkei 225 Index is 9.5x vs 16.4x for the S&P 500” which attracts PE investors to the region. The other factor is: “The average age of CEOs in Japan is 64 years old – and approximately 1.5 million family-owned companies have not identified a successor.”

18. Fishing in Japan

“Due to Japan’s geographical features and proximity to desirable currents, fisheries traditionally play an important role in food security and are as old as Japanese culture itself.

The country’s coastline stretches over almost 30,000 kms, and no Japanese territory is further than 120 kms from the sea. Because of the cold ocean current Oyashio from the north colliding with the warm ocean current Kuroshio of the Pacific Ocean, the waters surrounding the archipelago are among the world’s most productive and varied fishing grounds.”

Once the world’s largest fishing nation when it reached its peak production in 1984 producing 12.8 million tonnes, fishing in Japan is changing over time. The output declined to 4.8 million tonnes in 2012, and at the moment, stands closer to 4 million tonnes.

Japan’s fishing self-sufficiency has been declining. From being an exporter until 1970s, sometime in the last two decades, Japan became the world’s largest importer of fish and fish products. And then since, changing food habits throughout the world and changing demographics, Japan is now the third largest importer of aquatic produce ($15 billion).

“Japan was the world’s largest fishing nation from the 1930s through the 1980s, is historically among the globe’s most voracious consumers of seafood, and has long been a central player in the international marine products trade, both as a leading exporter and as a major importer.”

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) came in 1982, and although Japan has a large EEZ, which is an area of the sea which a sovereign state has exclusive rights regarding exploration and use of marine resources, of 4.4 million km squares, which is eighth largest in the world (largest EEZ being France’s 11.6 million km sq, US with 11.3 million km sq), it reduced access to international waters for Japan and led to overfishing.

“Until the early 1970s, Japan was a net supplier of fish and seafood products, but when the 200 nautical mile EEZ was implemented it changed Japan from a net-exporter to a net-importer.”

Over time, the number of fishing vessels owned in Japan has gone down (from 416,000 registered boats in 1990 to 132,000 in 2018). The per capita consumption of seafood in Japan dropped from 66 kgs in 2000 to ~41 kgs per capita in 2021 (some explained by rising meat consumption). Although this shows a trend different from the rest of the world where fish consumption is going up, especially in China (which is now at same level as Japan), Indonesia (which is now more than Japan), and the US (now at 22kg).

Like agriculture, fishing in Japan is also seeing severe labour shortages (number of people working in fishing dropped by 53% in a quarter of century) – primary factors being ageing and emptying out of fishing villages. At the moment, ~123,000 people work in fishing (down from 238k in 2003). To counter these effects, the fishing sector is relying more on foreign labour. It is estimated that the government provides ~$1.3 billion of support to fishing.

Over time, aquaculture has changed the way fish is supplied. Although historic, it changed over the last two decades, with 2014 marking the year when aquaculture globally overtook captured fish. Until 1980, it was 7% of total fishing output. China being the main place where it has changed). Japan has ~900k tonnes from aquaculture against ~3.1 million tonnes from direct fishing. China farms 73 million tonnes from aquaculture and 13.4 million from direct fishing. Like for many other industries in the world, China has changed the face of fishing over the last 3-4 decades.

“China is the world’s dominant fishing power. By several measures, the scale and reach of its fishing economy surpasses that of any other nation. In marine capture fisheries, it produces 15% of world catch, nearly twice the catch of the next largest fishing nation, Peru. Its fleets are distributed across China’s four regional near seas, in distant waters under the jurisdiction of other countries, and on the high seas. In marine and freshwater aquaculture, China produces more farmed aquatic food than the rest of the world combined. Its marine fishing labor force includes over one million workers on 200,000 fishing vessels, while the broader fishing and aquaculture industry employs nearly 15 million workers. China is now the largest exporter and third largest importer of fish and fish products. However, China’s centrality in seafood trade is a relatively recent phenomenon and reflects a complementary combination of natural economic advantage and government industrial policy.”

Perhaps, here a little note on whaling as well since whaling has been important to Japan:

“In the 1960s, the whaling and fishing industries were holders of substantial power in the country. In the beginning of the 1960s the Japanese whale meat consumption was at its peak, being eaten more than any other meat. In the middle of the decade however it became more evident how scarce were resources becoming and a ban on some whale species was introduced. By the 1970s environmental concern over hunting whale practices was manifested by international organisations and overall negative sentiment over whaling was shared in the West. In 1975 the price of chicken meat was for the first time cheaper than whale meat. However, the amount of whale meat consumed remained constant. In 1986, a moratorium on commercial whaling for five years was adopted, mainly promoted by the United States. The Japanese negotiators had to agree to this as the American officials threatened to terminate the Japanese fishing quota in the Exclusive Economic Zone of the US. The fish caught in those waters were more valuable than the exclusive whaling mandate. After this, Japanese commercial whaling had to stop, but the government was unwilling to terminate the practice altogether, so they continued hunting allegedly for science.

Although commercial whaling in Japan ended in 1987, it still catches whales. In 2000, the Japanese whale catch of over 16,700 represented about 82% of the world’s whale catch. Japan is one of three countries – along with Norway and Iceland – that continues to hunt whales, and officials argue that the industry is an important part of its culture and history – and also provides food security.”

19. Bullet Trains

First built in 1964 for the Tokyo Olympics, in 2024, bullet trains (Shinkansen) were celebrating their 60 years.

“From 1964, when the first bullet trains made their inaugural journey: “Hundreds of people had waited overnight in each terminal to witness this historic event, which, like the Olympics, heralded not just Japan’s recovery from the destruction of the second world war, but the beginning of what would be Japan’s stratospheric rise as an economic superpower. The journey between Japan’s two biggest cities by train had previously taken close to seven hours. The Shinkansen had made the trip in four.””

With speeds now reaching 320 km/hr, the Japan bullet train/ Shinkansen covers 3,000kms. (The total rail network in Japan is close to 30,000 kms).

It is interesting that rail transport in Japan is not used as much for freight transport (<1% per one data source, and 6.2% modal share). It is primarily used for high-speed travel between cities by passengers and for commuter transport in cities. “The average Swiss person travels 2,430 km by train each year (the highest in the world), almost 500 more than the average Japanese person (the second highest).”

Although rail usage across the world is differently organised – US being the largest network in the world (149,000 kms, of which only 735 kms is high speed) but primarily for freight with relatively negligible passenger transport. China is becoming the world’s largest high-speed transport network (total rail network of 110,000 kms, high speed network of 40,500 kms with plans to reach 70,000 kms by 2035). Spain is the second largest high-speed rail network with over 3,600 kms.

Perhaps given the network and efficiency of its rail network, the modal share of railway transport (not including metro network) is the highest in Japan at 33%. China, with its spread, and the world’s biggest network of high speed passenger trains is at 32%. In the US, it is only 0.3%.

Carrying 420,000 passengers on a typical weekday, Bullet trains/Shinkansen carried 356 million passengers in Fiscal 2023. For comparison, in 2023, Japan airports handled around 284 million passengers. (And global air travel passengers are c. 5 billion)

“While China does operate some of the fastest trains worldwide, including the CRRC Qingdao Sifang 2021 Maglev, the title of fastest train worldwide is taken by Japan. Japan’s L0 Series Maglev can reach speeds up to 603 kilometers per hour, marginally faster than China’s fastest Maglev, which can go up to 600 kilometers per hour.”

Here, perhaps a quick note on the Subway networks in Japan as well.

“Public transport within Greater Tokyo is dominated by the world’s most extensive urban rail network. Tokyo’s rail system carries around 40 million passengers daily. This includes the subway, monorail, and other commuter rail systems.”

But Tokyo Metro (which is a small section of the larger Tokyo rail rapid transit system) has ~6.84 million daily commuters. It used to be one of the world’s busiest networks, but now Shanghai and a few other metro systems in China are busier. Shanghai hit a daily ridership record of 13 million in 2024. Add to it the Toei subway lines which brings in 3 million more daily commuters. These subways make up a relatively small fraction of heavy rail rapid transit in Tokyo alone—only 286 out of 938 railway stations. And the world’s busiest station – Shinjuku station is based in Tokyo. It sees over 3.5 million visitors daily.

20. Power generation in Japan

In terms of natural resources, Japan has negligible mineral resources and virtually no natural energy resources, making it almost completely dependent on imported energy sources. Amongst the larger economies of the world, perhaps Japan is one with very limited natural resources.

Japan is the fifth largest country worldwide in terms of electricity generation (>1,000 terra watt hours). For comparison China generates 9,456 terra watt hours, US 4,494 terra watt hours and third largest India, close to 2 pettawatt hours.

Globally, coal remains the world’s single largest electricity generation source contributing to 34% of global electricity. (10 out of 29.5 petta watt hours of global electricity production), followed by gas (22% – 6.6 PWH). Coal, gas and oil contribute 61% to global electricity, nuclear 8.8% (2.6 PWH) and rest by renewables (~30%).

In Japan, 69% of electricity is generated from fossil fuels which are imported. The electricity generated by coal in Japan (274 TWH) is fourth largest in the world (~29% of total electricity in Japan). Amongst renewable sources, Japan has solar power contributing to ~10.8% of electricity generation.

“Resource-poor Japan is dependent on imports for 94% of its primary energy supply. Japan’s energy supply structure is extremely vulnerable. Following the two oil crises in the 1970s, Japan has diversified its energy sources through increased use of nuclear energy, natural gas and coal, as well as the promotion of energy efficiency and conservation.

The “Strategic Energy Plan” decided by the government in April 2014 also states that nuclear power is as important base load power source that can, strictly premised on safety, contribute to the stability of the supply and demand structure of energy.

In June 2015, a plan was announced to maintain the proportion of nuclear power at 20 to 22% in the energy mix in 2030.”

At its peak, nuclear power contributed c.26% to electricity in Japan (2009 numbers). Nuclear power used to be a national strategic priority but things changed following 2011 Fukushima. Currently nuclear power is at 7.6% in Japan.

Globally, the largest nuclear power production happens in US (772 TWH, 18.6% of its electricity generation), China (395 TWH, ~5%) and France (282 TWH, 70 % of its electricity generation). As an aside, currently the world has ~440 commercial nuclear reactors, 220 research reactors and over 160 ships (mostly submarines) propelled by ~200 nuclear reactors.

The percentage of renewable energy power in Japan was 19% in FY 2020. Japan ranks sixth in the world in terms of renewable energy generation capacity, and third in the world for solar power generation. Japan is also leading the way in technological development and dissemination of power storage systems in its efforts to expand the use of fuel cells and Ene-Farms with 2.4 GWh installations of home power storage systems – the highest in any major market.

It is an intermediate step to eventually shifting to a primarily renewable power generation set.

For the 2030 electricity generation, the goal in Japan is for renewables to contribute 330-350 billion KWH contributing 36-38% from current 20%.

(Perhaps something to consider here is the changing wealth of nations, the relative significance of natural resources, agriculture (important for national security), in terms of wealth, the urban infrastructure (and related real estate values), the economy and capital markets (and relative equity values), the industrialisation and services (financial sector and value created in services and high value industries) – public & private investment driven value creation in most of the developed world.)

21. Steel Industry in Japan

Japan was the world’s largest producer of steel in early 1990s taking over from the previous leader USSR. Since 1995 though, changes in China as they changed the structure of many industries in the world, changed the steel industry significantly as well. At its peak, Japan was producing ~110 million MT of steel. Currently, Japan is the third largest producer of steel in the world at ~87 million MT. China, from almost half of Japan’s production in 1990, went on to grow significantly, and consistently fuelled its infrastructure demand with steel production of now reaching 1,000 million MT per annum. This implies the global production of steel has gone up from ~500 million MT in 1960s to 850 million MT in 2000, and since then with China adding hundreds of million MT every year, to 1.4 billion MT in 2010, and around ~1.9 billion MT at the moment (!). Pretty much the growth is driven by China demand.

Although it seems to now slow down, and for the first time in a few years, China demand has fallen below 50% of global demand.

The market size of the Japanese steel industry is $83 billion. The global steel market in dollar terms is $1.5 trillion.

Although Japan is the world’s third largest steel exporter, for raw material, iron and coal, it still relies on imports.

The key players in the Japan steel market are Nippon Steel (largest in Japan, fourth largest in the world, capacity of 44 million MT) and JFE Steel Corporation (25 million MT capacity). Nippon Steel has been working for a year to acquire US Steel which could make it the world’s third largest steel player, but US is expected to block the deal.

As an aside, the steel sword-making techniques came to Japan through China and Korea in c. sixth century, but were perfected over many iterations making Japanese swords some of the finest in the world combining high strength with high flexibility, a blend of technology and art. The steel-sword making was ritualised to reflect the right amount of carbon and iron proportions.

“It has been said that the samurai’s sword was his soul. Perhaps this deep attachment had something to do with the perfect melding of form and function found in the katana, as the famous curved sword is known in Japan. Invented a millennium ago, the katana remains a marvel of aesthetic beauty and skillful engineering. While most bladed weapons over the centuries were designed to either pierce or slash, the katana’s two different types of steel gave it optimum qualities for both, making it a highly versatile weapon in battle.”

22. Automobile Industry in Japan

The Japanese automobile sector is a key pillar to the country’s economy. At over $400 billion, it is the third largest auto sector in the world employing about 5.6 million people or 8% of the working population in Japan (of these 5.6 million people, road transport employed 2.79 million people). There are 78 factories in Japan. Automotive shipments (both domestic and exports) account for 17.4% of total Japan manufacturing. Investments in this sector translates to 20-30% of overall investment in Japan’s manufacturing sector.

In terms of context for Japan’s Automobile industry – the first car was brought to Japan in 1898, after the first automobile was invented in Germany in 1880s. The WWII focus was mainly on trucks and motorcycles for army, and in 1950s, Japan’s annual vehicle production was merely 10,000, but the key change came in 1960s, with the launch of Japanese Kei cars (light vehicles), making it affordable for more people to own cars. This boosted sales which in turn boosted the industry. In 1960s, the export spurt came with ~20% of cars being exported. 1960s was also the time when the “era of technological tie-ups” came to an end in Japan, with focus shifting to complete domestic production.

“Japan ranked sixth in 1962, surpassing Italy the following year to take fifth place; surpassing France in 1964 to take fourth place; surpassing the United Kingdom in 1966 to take third place; and surpassing West Germany in 1967 to rank second in the world after the United States, whose production Japan would also surpass in 1980 to become the world’s largest producer of automobiles.

Despite this tremendous rise in output, Japanese automobile production differed from that of other countries in terms of the type of automobiles produced (a high percentage of cars with small engine displacement), production infrastructure (multiple-model, small-lot production and small factory size), and the fact that there continued to be mixed, non-stop production of cars and trucks. Even Japanese used cars were also been used frequently.”

For around fifteen years, late 1970s to early 1990s, Japan was the world’s leading producer of cars/light vehicles (from 5.3 million in 1970s to a peak of 13.5 million units in 1990), surpassing US, the previous leader (in 1950, US produced ~75% of global light motor vehicles). Things changed from 1995 onwards, with US taking the lead again. For Japanese companies, offshore plants began to appear from 1985 onwards. And in this millenium, things have shifted again with China now surpassing both US and Japan. China manufactures about a third (30 million) of global automobiles (Light vehicles). Japan manufactures ~9 million units. But perhaps here to also consider that Japanese companies overseas production is ~17.5 million units.

In terms of exports, Germany is the world leading car exporter with $149 billion, followed by Japan at $89 billion (2022, cars only). But recent data shares that in terms of number of vehicles, now China has surpassed Japan. China – 4.91 million vehicles exported in 2023, to Japan’s 4.42 million vehicles in 2023. So far in the recent decade, Japan had been the largest exporter by numbers. Cars are incidentally, the fourth most exported category (value) in the world.

Two notes here – Like other sectors, perhaps the boom in global GDP can owe itself to the rise of China in almost every sphere of consumption and production. Second, that many companies own international factories make the definition of exports and domestic consumption fluid – and hence this data is just directional.

In terms of key Japanese companies in the sector:

“The four major players or the Big Four in the automotive industry ate Toyota, Honda, Nissan and Suzuki. Then follows companies like Mitsubishi, Daihatsu, Mazda, Subaru, Isuzu and Lexus.”

Toyota as a company is the largest manufacturer of cars in the world. It sold over ~10 million units in 2023. Volkswagen (Germany) is the second largest with ~9 million units. Honda, global number 8 in terms of unit, is the second largest Japanese automaker with ~4 million units sold in 2023. Next is Nissan with ~3.3 million units. Still, if one considers the largest automaker in terms of market value, it is Tesla (though only 1.8 million units) with a market cap of $1.35 trillion. Toyota has a market cap of $238 billion with a revenue of $312 billion.

And yet, on one end is Japan’s position in the world as an automobile maker. And on another is Tokyo. Tokyo is a car-free city of sorts where only 12% of commute happens through cars. It is one of the distinctive features of Tokyo, relatively quiet residential areas and a buzzing city below the road levels where across two inner subway lines, 9 million passengers commute daily (almost 40 million if the larger city is considered).

“It may come as a surprise that Japan is home to the world’s biggest relatively car-free city. After all, Japan is the country that gave the world Mitsubishi, Toyota, and Nissan, and exports vehicles all over the world. And in fairness, a lot of Japanese people do own cars. Overall car ownership in Japan is about 590 vehicles per 1,000 people, which is less than America’s rate of about 800 per 1,000, but comparable to a lot of European countries. On average, there are 1.06 cars per household. But Tokyo is a big exception. In Tokyo, there are only 0.32 cars per household.”

23. Capsule context of Japan’s history

“Japan has about two millennia of recorded history which proceeded from rice cultivation to warfare among small states and national unification under Emperor. Then decentralization began, samurai emerged, feudalism was installed and industrialization and modernization started in the nineteenth century under Western influence.

Throughout its history, Japan also experienced periods of relatively tranquil internal evolution and periods of dynamic change under strong external influence. These periods alternated to create Japanese society in a multi-layered fashion.

Major external impacts on Japan included the following:

Rice cultivation—introduced from the Eurasian Continent around the third century BC (recent evidence shows that arrival of rice cultivation may have been earlier).

(Meanwhile, internally in Japan: In Shinto, Japan’s oldest religion, people identify kami (divine forces) in nature and in such human virtues as loyalty and wisdom. Between 100-300 AD, local clans form small political units.)

Buddhism—brought from China via Korean Peninsula in the sixth century AD.

Chinese culture and political system—imported vigorously from the seventh to the early tenth century AD.

(Meanwhile, internally in Japan: Periods of Asuka, Nara and Heian (seventh to twelfth century) – period of emperors, strengthening of Imperial Courts. Also, Buddhism, in combination with native Shinto beliefs, continues to flourish.

Late 12th century – Kamakura military government established. Followed by Takauji (Kyoto)’s military government from 1333 to mid-sixteenth century.)